By ISSF Admin @mujifren

Prologue: The Smog of Deception

In the choking winter smog of Dhaka, December 2025, the air did not just smell of exhaust and burning refuse; it reeked of a nation decomposing.

To the uninitiated observer, the chaos gripping Bangladesh might have appeared as the tragic growing pains of a “Second Revolution,” a messy transition following the ouster of Sheikh Hasina in 2024.

But to the trained eye of the geopolitical realist, and certainly to the security establishment in New Delhi, the events of December were something far more sinister: the final shedding of Bangladesh’s secular skin and the emergence of a radicalized, irredentist hydra on India’s eastern flank.

The catalyst for this descent into anarchy was a singular event: the assassination of Sharif Osman Hadi.

Hadi was not the democratic saint the Western press has tried to paint him as.

He was a 32-year-old firebrand, an Islamist radical disguised as a student leader, and the architect of a vision so dangerous it threatened to redraw the maps of South Asia in blood.

When a bullet tore through his skull on the afternoon of December 12, it did not just kill a man; it detonated a pre-loaded charge of anti-India hysteria that the interim government of Muhammad Yunus was too weak — or perhaps too complicit — to defuse.

This report is a forensic deconstruction of that murder and its aftermath. It is an investigation into the lie that claimed India pulled the trigger — a lie manufactured to cover up a gangland hit in the heart of Dhaka.

It is a chronicle of how that lie was weaponized to burn down the pillars of Bengali culture and to lynch a Hindu worker named Dipu Chandra Das, whose charred body hanging from a tree in Mymensingh became the true flag of the “New Bangladesh”.

This is not merely a crime report; it is an autopsy of a neighbor gone rogue.

Chapter I: The Architect of Hate – Who Was Sharif Osman Hadi?

To understand why Dhaka burned for Hadi, one must understand what Hadi represented. In the sanitized dispatches of agencies like AFP or Reuters, he is often referred to as a “pro-democracy figure” or a “student leader”.

These labels are woefully inadequate, masking the toxic ideology that drove him. Sharif Osman Hadi was the tip of the spear for a new generation of Bangladeshi radicals who view India not as a liberator (as in 1971), but as an existential enemy and a colonial overlord.

1.1 The Genesis of a Radical

Born in 1993 in Nalchity Upazila, Jhalokhati, Hadi was the son of a madrasa teacher and a local imam.

His upbringing was steeped in the rigid, dogmatic environment of the madrasa system, a world often hermetically sealed from the secular traditions of Bengali culture.

While he later attended the University of Dhaka, the seed of religious hardline thought had been planted early.

Hadi did not rise to prominence through student union elections or academic debate.

He was forged in the fire of the July 2024 uprising.

While thousands of students marched for quota reforms, Hadi and his faction saw an opportunity for something darker: a complete systemic overhaul that would purge Bangladesh of its “Indian-backed” secular constitution.

He co-founded and became the spokesperson for Inqilab Mancha (Revolutionary Platform).

The name itself — Inqilab (Revolution) — harkens back to Islamist struggles rather than liberal democratic movements.

Under his leadership, Inqilab Mancha positioned itself to the right of even the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP).

Hadi was not interested in a transfer of power; he wanted a purification of the state.

1.2 The Ideology of “Anti-Indian Hegemony”

Hadi’s political brand was built on a single, obsessive pillar: hatred of India. He framed every political failure in Bangladesh —from economic stagnation to the endurance of the Awami League — as a symptom of “Indian hegemony”.

This was not subtle diplomatic criticism. It was visceral, xenophobic incitement. In public rallies at Shahbagh and press conferences at the Madhur Canteen, Hadi utilized a rhetoric that bordered on war-mongering.

He warned the BNP — the presumed successors to power — that if they returned to “old-style politics” (a euphemism for maintaining functional ties with New Delhi), they would not last two years.

He was effectively holding a gun to the head of any future government, demanding a permanent freeze in Dhaka-Delhi relations.

1.3 The “Greater Bangladesh” Map: A Declaration of War

The most dangerous aspect of Hadi’s activism – and the one that likely made him a liability to the more pragmatic elements of the Bangladeshi deep state – was his open advocacy for “Greater Bangladesh” (Vishal Bangla).

Weeks before his assassination, Hadi circulated a controversial map on Facebook and in pamphlet campaigns.

This map was a cartographic hallucination that reimagined the borders of South Asia.

It did not respect the Partition of 1947 or the Liberation of 1971. Instead, it depicted a Bangladesh that had swallowed:

- The Seven Sisters: The entire Northeast of India (Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh).

- West Bengal: Including Kolkata, the cultural heart of the Bengali Hindu identity.

- Parts of Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha: Stretching the borders deep into the Indian heartland.

Table 1: The Components of Hadi’s “Greater Bangladesh” Vision

| Territory Claimed | Strategic Significance | Ideological Justification |

| West Bengal (India) | Economic Hub (Kolkata), Cultural Capital | Reunification of Bengal under Islamic rule (reversal of 1947). |

| The “Seven Sisters” | Resource rich, Strategic vulnerability for India (Siliguri Corridor) | Creating a land bridge to China; ending Bangladesh’s “landlocked” status vis-a-vis India. |

| Arakan (Myanmar) | Rohingya homeland | Pan-Islamic solidarity; expansion to the east. |

Security analysts in New Delhi viewed this not as a prank, but as a sophisticated psychological warfare campaign (PSYOP) likely backed by hostile foreign intelligence agencies (ISI or MSS) to destabilize India’s eastern flank.

By disseminating this map, Hadi was moving from political activism to sedition against a neighboring nuclear power. He was radicalizing a generation of youth to view the conquest of Indian territory as a legitimate political goal.

1.4 The Independent Candidacy: A Fatal Ambition

In the volatile ecosystem of Dhaka politics, ambition is often a death sentence. In preparation for the February 2026 general election, Hadi announced his candidacy as an independent for the Dhaka-8 constituency.

Dhaka-8 is not just a parliamentary seat; it is the nerve center of the capital.

It encompasses Motijheel, Paltan, and Shahbagh — the financial, political, and cultural hubs of the country.

Controlling Dhaka-8 means controlling the streets, the extortion rackets, and the student unions.

By running for this seat, Hadi was challenging the entrenched warlords of the BNP, the Jamaat-e-Islami, and the surviving remnants of the Awami League syndicates.

He was a “Third Force”—uncontrollable, radical, and vastly popular among the angry, unemployed youth.

To the established political mafia of Dhaka, he was a threat to their monopoly on power. And in Dhaka, threats are neutralized.

Chapter II: The Kill Box – A Cinematic Reconstruction of December 12

The assassination of Sharif Osman Hadi was not a crime of passion.

It was a cold, calculated execution carried out with a precision that belies the “chaotic mob” narrative often associated with Bangladesh.

It was a professional hit, timed for maximum political impact.

2.1 The Setup: Friday, December 12, 2025

The date was significant. Just twenty-four hours earlier, on December 11, the Election Commission had announced the schedule for the 13th National Parliamentary Election.

The starting gun had been fired. Every political faction in Dhaka was scrambling to secure turf.

Hadi spent the morning of Friday, December 12, at the Motijheel WAPDA Mosque for Jummah prayers. The mosque is a known gathering point for political mobilizing.

After prayers, Hadi launched what was to be his first major campaign rally.

He stepped out onto the streets of Motijheel, surrounded by supporters, the air thick with the humidity and the noise of a city that never sleeps.

2.2 The Trap: Box Culvert Road

At approximately 2:20 PM, Hadi boarded a battery-operated auto-rickshaw. This choice of transport is telling.

Despite his high profile and the death threats he had reportedly received, he was traveling in a slow, open-sided vehicle that offered zero protection.

He was heading towards Suhrawardy Udyan, the historic park where Sheikh Mujibur Rahman once called for independence—a symbolic destination for a man who believed he was leading a new war of liberation.

The rickshaw moved sluggishly through the traffic congestion near the DR Tower on Box Culvert Road, in the Purana Paltan area.

This is a “kill box”—a narrow choke point where traffic frequently grinds to a halt, trapping vehicles between concrete medians and high-rise buildings.

2.3 The Execution

As the rickshaw slowed near the Bijoynagar water tank, the assassins made their move.

They did not come in a car; they came on a motorcycle — the preferred vehicle of hitmen in the subcontinent due to its ability to weave through gridlock and escape down narrow alleyways.

There were two men on the bike. The driver was later identified as Alamgir Sheikh.

The shooter, riding pillion, was identified as Faisal Karim Masud (alias Daud), a former leader of the Chhatra League (the student wing of the Awami League).

The motorcycle pulled up alongside the rickshaw on the right side. The shooter did not spray and pray.

He was composed. He raised a firearm — likely a 9mm pistol — and fired at point-blank range.

The bullet struck Hadi in the head. It entered above the left ear, traversed the skull, and exited through the right side. The trajectory severed the brain stem. It was a kill shot.

Hadi slumped forward in the rickshaw, blood pooling on the vinyl seat, as the chaos of the street erupted around him.

The entire attack took less than ten seconds. The motorcycle sped off, vanishing into the labyrinth of Purana Paltan, leaving behind a dying man and a nation on the brink of an inferno.

2.4 The Medical Drama and the “Singapore” Factor

Hadi was rushed to Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), the epicenter of trauma care in the city. But the damage was catastrophic.

As news spread, thousands of Inqilab Mancha activists laid siege to the hospital, chanting, weeping, and demanding vengeance.

The interim government, led by Muhammad Yunus, panicked. A dead martyr on the streets of Dhaka is a dangerous thing.

To buy time and perhaps to show they were doing everything possible, the government authorized an air ambulance evacuation.

On December 15, Hadi was flown to the Singapore General Hospital.

For three days, he lay in a coma, a silent figure hooked up to machines in a sterile room in Singapore, while in Dhaka, the knives were being sharpened. On December 18, his organs failed. He was pronounced dead.

The fuse was lit.

Chapter III: The Anatomy of a Lie – The “Indian Escape” Fabrication

Immediately following the shooting, a narrative began to take shape—a narrative so convenient, so politically expedient, and so factually bankrupt that it could only have been engineered by a state apparatus desperate to deflect blame. This was the lie of the “Indian Escape.”

3.1 The “Awami League” Scapegoat

The Bangladeshi police, a force thoroughly demoralized and politicized, quickly identified the suspects: Faisal Karim Masud and Alamgir Sheikh.

They were labeled “active members of the Awami League”.

In the post-2024 Bangladesh, the Awami League is the universal scapegoat. Banned, disbanded, and hunted, the party serves as a convenient boogeyman. By pinning the assassination on a former Chhatra League leader, the investigators achieved two goals:

- They absolved the current regime and its internal factions (like the BNP or NCP) of any involvement.

- They linked the killing to Sheikh Hasina, and by extension, to India, her alleged protector.

3.2 The Impossibility of the Haluaghat Crossing

The police narrative claimed that within hours of the shooting at 2:20 PM in central Dhaka, the assassins managed to flee the city, change vehicles five times, and cross the border into India via the Haluaghat crossing in Mymensingh.

From a forensic and logistical perspective, this claim is absurd. Let us break down the geography:

Table 2: Logistical Analysis of the Alleged Escape Route

| Parameter | Data Points | Feasibility Verdict |

| Origin | Purana Paltan, Dhaka (Crime Scene) | Center of gridlock. |

| Destination | Haluaghat Border, Mymensingh | Remote northern border. |

| Distance | 170 km – 230 km (depending on route) | Significant distance. |

| Travel Time | 4 to 6 hours (by road, optimal conditions) | Impossible in “hours” post-crime. |

| Traffic Conditions | Friday afternoon (Post-Jummah) | Peak congestion; exiting Dhaka alone takes 2+ hours. |

| Border Status | BSF High Alert (Red Alert status) | The border is fenced, floodlit, and patrolled by BSF. |

To believe the police narrative, one must believe that two high-profile assassins, minutes after a political assassination in the capital, navigated the world’s worst traffic, evaded all checkpoints, drove for five hours to a remote border post, and slipped past the Border Security Force (BSF) of India—all before the sun went down.

This was not an investigation; it was a script.

3.3 The Geopolitical Weaponization

The purpose of this fabrication was clear: Incitement.

By claiming the killers “fled to India,” the radical factions (Inqilab Mancha, NCP) could redirect the anger of their supporters away from the incompetence of the Yunus government and towards New Delhi.

It transformed a domestic gangland killing into a violation of sovereignty by a “hostile neighbor.”

India’s Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) was forced to issue a rare and sharp rebuttal, stating categorically that India has “never allowed its territory to be used for activities inimical to the interests of Bangladesh”.

Even the Dhaka Metropolitan Police later quietly admitted there was “no evidence” the shooters were in India. But in the post-truth world of Bangladeshi politics, the retraction never catches up to the lie. The mob had their casus belli.

Chapter IV: The Night of Broken Glass – The War on Truth and Culture

When the news of Hadi’s death in Singapore broke on the night of December 18, the streets of Dhaka did not mourn; they raged. The violence that followed was not random looting.

It was a highly specific, targeted pogrom against the institutions that represent the secular, liberal soul of Bengal – institutions that the Islamists view as proxies for “Indian influence.”

4.1 The Burning of the Fourth Estate

The primary targets were the offices of Prothom Alo and The Daily Star, the two largest and most respected newspapers in the country.

These papers have a history of independent journalism and secular editorial stances.

To the radicals of Inqilab Mancha, they are “agents of Delhi.”

The Siege of Karwan Bazar:

Around midnight on December 18, thousands of protesters, fueled by the hysteria of Hadi’s death, surrounded the multi-story complex housing these newspapers.

They chanted slogans that conflated journalism with treason: “Dilli na Dhaka? Dhaka Dhaka!” (Delhi or Dhaka? Dhaka!).

They did not just chant. They attacked.

Mobs smashed the glass facades and set the lobby on fire.

The flames licked up the sides of the building, trapping journalists on the upper floors.

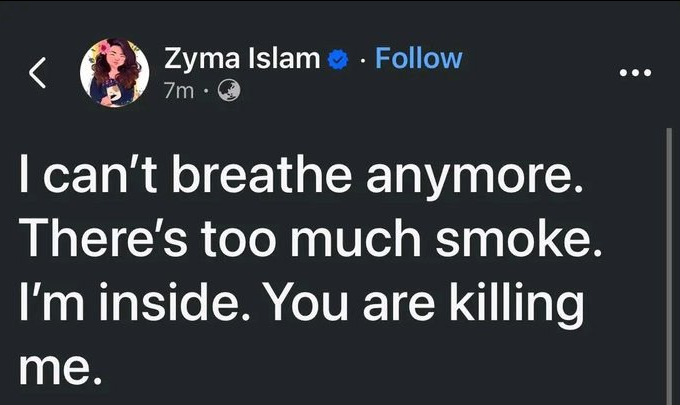

“I Can’t Breathe”:

Inside the burning building, Zyma Islam, a reporter for The Daily Star, posted a terrifying message on social media that went viral instantly: “I can’t breathe anymore. There’s too much smoke. I am inside. You are killing me”.

This was the visceral reality of the “New Bangladesh.” Journalists huddled on rooftops, choking on smoke, while “student leaders” cheered the flames from the street below.

Sajjad Sharif, the Executive Editor of Prothom Alo, called it the “darkest night” in the paper’s 27-year history.

For the first time ever, the newspaper failed to go to print the next morning. The voice of reason had been silenced by the roar of the fire.

4.2 The Desecration of Culture

The mob did not stop at the press. They turned their attention to the Chhayanaut cultural center in Dhanmondi.

Chhayanaut is not just a music school; it is the custodian of Tagore’s legacy in Bangladesh, the organizer of the Bengali New Year (Pahela Baishakh), and a symbol of the syncretic Bengali culture that connects Muslims and Hindus.

Radical Islamists have long hated Chhayanaut, viewing its celebration of Bengali culture as “Hindu-influenced” and un-Islamic. On the night of December 18, they smashed its instruments, burned its archives, and vandalized its auditorium.

Simultaneously, the offices of Udichi Shilpigoshthi (a leftist cultural group) and the charred remains of the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum (already attacked in August) were targeted again.

This was a Cultural Revolution, Taliban-style.

The message was clear: There is no room for “Bengali” identity in the new Islamist emirate; there is only “Muslim” identity, and anything that connects Bangladesh to its pre-Islamic or Indian heritage must be destroyed.

Chapter V: The Martyrdom of Dipu Chandra Das – The Blood Price of a Lie

While the burning of newspapers grabbed the international headlines, a far more grotesque tragedy was unfolding in the industrial belt of Mymensingh.

It is here that the abstract hatred whipped up by Hadi’s death materialized into the brutal murder of an innocent man.

5.1 The Victim: A Face in the Crowd

Dipu Chandra Das was 25 years old (some reports say 28). He was a Hindu. He was poor. He worked as a laborer at Pioneer Knitwears BD Ltd in the Bhaluka upazila of Mymensingh.

He was the sole breadwinner for his family, supporting a disabled father, a mother, a wife, and a child.

He was not a political activist. He had never drawn a map of “Greater Bangladesh.” He was simply trying to survive.

5.2 The Pretext: Blasphemy

On the night of December 18 — the same night the mobs were burning newspapers in Dhaka — a dispute broke out in the factory.

A Muslim coworker, reportedly over a trivial work-related disagreement, played the ultimate card: he accused Dipu of making “derogatory remarks about the Prophet”.

In contemporary Bangladesh, an accusation of blasphemy is a death sentence. It requires no proof, no trial, and no witnesses. It is a dog whistle that summons the lynch mob.

5.3 The Betrayal

The role of the factory management in this murder is a stain on the conscience of the nation. Alamgir Hossain, the floor manager, did not call the police to protect his employee. Instead, he forced Dipu to resign on the spot and then — in an act of calculated cruelty — handed him over to the agitated mob waiting outside the factory gates.

It was a ritual sacrifice. The manager washed his hands of the “problem” by feeding it to the wolves.

5.4 The Lynching

What followed was savagery. The mob, numbering in the hundreds, beat Dipu with sticks, bricks, and iron rods. But death was not enough to satisfy their bloodlust.

They dragged his broken, lifeless body to a tree near the bustling Dhaka-Mymensingh highway.

They hoisted him up, hanging him like a trophy. Then, they doused him in fuel and set him on fire.

As Dipu Chandra Das burned, the mob cheered. Traffic stopped. People filmed it on their phones.

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) later issued a statement confirming that there was “no evidence of blasphemy”.

Dipu was innocent. He was murdered not because he insulted the Prophet, but because he was a Hindu in a country that had just been told by its leaders that “India” (and by extension, Hindus) had killed their hero, Hadi.

The lie about Hadi’s assassination created the atmosphere of hate that consumed Dipu Das.

Chapter VI: The Siege of Diplomacy – India Under Attack

The assassination of Hadi was quickly weaponized into a direct diplomatic and physical assault on India’s presence in Bangladesh.

The “Greater Bangladesh” map that Hadi had championed became the blueprint for the mob’s geopolitical ambitions.

6.1 The Assault on Sovereign Territory

Diplomatic missions are sovereign territory, protected by the Vienna Convention. In December 2025, that protection evaporated in Bangladesh.

- Chittagong: A mob, enraged by the rumors of the assassins fleeing to India, besieged the residence of the Indian Assistant High Commissioner. They hurled bricks, shattered windows, and attempted to storm the compound. The Bangladesh police were forced to use tear gas to prevent a full-scale overrun of the diplomatic post.

- Dhaka: The National Citizen Party (NCP), led by radicals like Hasnat Abdullah, organized a march toward the Indian High Commission in Gulshan. Abdullah publicly threatened to “behead Delhi” and “break the Seven Sisters”.

This was not a protest; it was a siege. The interim government’s failure to prevent mobs from reaching the gates of the High Commission signals a terrifying reality: the state has lost its monopoly on violence, or worse, it is using these mobs as a tool of foreign policy.

6.2 The Threat to the “Seven Sisters”

The rhetoric coming out of the Inqilab Mancha and NCP is explicitly irredentist.

They are not just asking for a change in government; they are calling for the balkanization of India.

By invoking the “Seven Sisters” (India’s Northeast), they are reviving the dormant ghosts of insurgency.

Bangladesh, under Hasina, had been a crucial security partner for India, cracking down on groups like ULFA.

A hostile Bangladesh, radicalized by figures like Hadi, could once again become a sanctuary for separatists, gun-runners, and terrorists aiming to destabilize Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura.

Table 3: The Strategic Threat Matrix for India

| Threat Vector | Description | Impact on India |

| Diplomatic Security | Attacks on High Commissions | Risk to life of Indian envoys; forcing mission closures. |

| Border Instability | “Greater Bangladesh” claims | Increased border incursions; mobs trying to cross fencing. |

| Refugee Crisis | Violence against Hindus | Potential influx of refugees into West Bengal/Assam. |

| Insurgency | Safe haven for Northeast rebels | Resurgence of violence in the Seven Sisters. |

6.3 India’s Response: The Sound of Closing Doors

New Delhi has responded with the cold, hard logic of a state that realizes its neighbor is lost.

The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) summoned the Bangladeshi envoy and issued a stern demarche.

India suspended visa operations in Rajshahi, Khulna, and temporarily in Dhaka, effectively sealing the people-to-people channel.

Crucially, while Dhaka burns, India is looking elsewhere. In the same month (December 2025), India signed a massive Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Oman and a trade deal with the UK.

This is a strategic signal. India is integrating with the Gulf and the West, expanding its economy and influence globally, while Bangladesh slides into isolation and poverty.

The contrast is stark: India is signing billion-dollar deals; Bangladesh is burning its own factories and lynching its own workers.

Chapter VII: Who Really Killed Sharif Osman Hadi?

If we dismiss the “Indian Hand” theory as the fabrication it clearly is, we are left with the question: Who actually killed Sharif Osman Hadi? The answer lies in the murky, cutthroat world of Dhaka’s internal politics.

7.1 The “Third Force” Threat

Hadi was a “Third Force.” He hated the Awami League, but he also despised the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami. He famously stated that if the BNP returned to power, they would be toppled in two years.

To the BNP, which has been waiting 17 years to regain power, Hadi was a spoiler. He was a loose cannon who could mobilize the street against any government.

In the ruthless calculus of power, he was an obstacle that needed to be removed before the election.

7.2 The Internal Purge

The “July Revolution” coalition is fracturing. The snippets reveal deep tensions between Inqilab Mancha and the National Citizen Party (NCP).

They are fighting over the same constituency: the angry youth. Reports suggest conflicts over extortion turf in Motijheel and Paltan – the very area where Hadi was shot.

It is highly probable that Hadi was killed by a rival faction within the “revolutionary” movement—a classic case of the revolution eating its own children.

The use of a “former Chhatra League” gunman (Masud) was likely a hired gun situation, a mercenary act rather than an ideological one.

7.3 The Martyrdom Strategy

There is also the chilling possibility that radical elements wanted a martyr. The anti-India movement needed a fresh infusion of blood to sustain its momentum.

Hadi alive was a troublesome independent candidate; Hadi dead is a perfect symbol, a “Martyr of Sovereignty” whose image can be used to whip up anti-India frenzy and consolidate Islamist power.

Conclusion: The Fire Next Door

The assassination of Sharif Osman Hadi was a tragedy, but the reaction to it has been a catastrophe. It has exposed the fragile lie of the “New Bangladesh.”

There is no democracy blooming in Dhaka; there is only the rule of the mob.

For the Hindu minority, represented by the ashes of Dipu Chandra Das, the future is terrifying.

They are now hostages in their own land, liable to be lynched whenever a political distraction is needed.

For the free press, represented by the charred offices of Prothom Alo, the message is “conform or burn.”

For India, the illusion of a friendly neighbor is over. The “Golden Bengal” has been cannibalized by a radicalism that views India’s destruction as its holy duty.

As the winter fog settles over the grave of Hadi and the scorched tree in Mymensingh, one truth remains clear: The killers of Sharif Osman Hadi are not in Delhi.

They are in Dhaka, sitting in the very offices and mosques that claim to mourn him. And they are just getting started.