By Nishant Kumar Hota

In Iran’s modern history, the recurring fact is simple and unromantic. Protest begins in the street, but it is the Bazaar that decides whether a revolt lives or dies.

In the rough triangle of the Palace, the Mosque, and the Bazaar, the merchants form the most practical link between belief and power, between doctrine and the stoppage of money. The 1979 Revolution showed this most clearly.

The Bazaaris, with their money, their links to the clergy, and their networks, turned what might have been another failed uprising into the end of the Pahlavi state.

Looking at 1979 beside the 2022 “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests and the 2025–2026 economic strikes, a pattern emerges that is not flattering to romantic theories of revolt.

Protests in Iran begin with anger over rights, morality, or politics. They become decisive only when the Bazaar is forced to withdraw its labor and capital.

The 2022 movement damaged the regime’s image and its moral standing but left its core intact because the Bazaar stayed largely outside.

By contrast, the strikes that began in late 2025, amid hyperinflation and a breakdown of calculation, brought back the old vulnerability: the state’s dependence on a functioning marketplace.

Historical Precedents of Bazaari Decisiveness

Iran’s Bazaar is not only a place of trade. It is a social and religious institution with a long memory. It draws in different classes , from rich wholesalers to poor laborers , and compresses them into a shared space in which complaint, rumor, and calculation circulate together. It is here that common grievances can be converted into action.

The 1891–1892 Tobacco Protest set the pattern. The Qajar Shah’s decision to grant a foreign monopoly in tobacco was not a distant policy mistake.

It cut directly into the merchants’ livelihood. The response was not an explosion of street rage but the disciplined closing of shops, organized in concert with the clergy. The alliance worked.

The Shah backed down and cancelled the concession. From that moment, it was clear that the Bazaar’s general strike , basteh , could halt royal income and disturb the social order more effectively than any slogan.

The Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911 strengthened this lesson. The Bazaar financed the protests and shut down trade to press for limits on royal power.

The clergy gave religious language to the new institution of parliament, speaking of justice and law in familiar Islamic terms. The result was Iran’s first constitution. Without the merchants’ money and their willingness to close their shops, the movement would likely have remained another failed petition.

| Historical Movement | Primary Trigger | Role of the Bazaar | Outcome for the State |

| Tobacco Protest (1891) | Foreign economic concessions | General strikes and clergy alliance | Cancellation of British concession |

| Constitutional Revolution (1905) | Arbitrary taxation and tyranny | Financial backing and market closures | Establishment of Parliament (Majles) |

| Oil Nationalization (1951) | Struggle for resource sovereignty | Support for Mossadegh’s coalition | Nationalization of oil industry |

| 1979 Revolution | Pahlavi modernization and repression | Financial backbone and logistics hub | Overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty |

| 2022 Protests | Death of Mahsa Amini (Social) | Largely quiet/unaffiliated initially | Regime survival; social laws unforced |

| 2025–26 Strikes | Rial collapse (Economic) | Structural strikes and market paralysis | Major budget and policy concessions |

The 1979 Revolution: The Archetype of Bazaari Support

The 1979 Revolution succeeded because three forces , the people, the clergy, and the Bazaar , moved together. Under the Pahlavis, the Bazaar was ignored rather than systematically organized from above, and so it kept its own networks and autonomy.

When the Shah’s “White Revolution” began to break the power of the traditional merchant class, these same networks turned against him. The result was not an abstract ideological revolt. It was a revolt grounded in money, logistics, and a religiously legitimated opposition.

The mechanics of the uprising were rooted in the Bazaar’s small associations and guilds. Religious societies, the hey’ats, provided the basic cells for organizing.

They arranged rituals and marches, kept contact, passed messages, and allowed the movement to survive over many months. In these circles, cassette tapes with Khomeini’s sermons were copied and distributed.

They reached people who could not read and those who were outside formal political circles. The Bazaar, connected in this way, became the nervous system of the revolution. The Islamic Coalition Societies coordinated much of this work, binding economic actors and religious activists.

The most important contribution was money. Religious merchants paid their tithes , khoms and zakat , directly to clerics, not to the state. Over time this built a pool of funds that freed the clergy from dependence on government.

These funds supported striking workers, prisoners’ families, and the relatives of the dead. It meant that strikes could last longer than a few days of lost wages.

This was the difference between symbolic protest and structural stoppage. That money paid, among many things, for Khomeini’s return flight. The Bazaar did not just support the revolution; it bought it time and continuity.

The 2022 Movement and Its Limits

The 2022 protests, after the death of Mahsa Amini, were of a different kind. This was an uprising against gendered control, against the policing of bodies and dress. It was more widespread geographically than many earlier protests, and it drew in the young, the urban middle classes, and sections of society that had grown up entirely under the Islamic Republic.

But the traditional Bazaar, as an institution, did not move in force. The grievances of 2022 were moral and social before they were economic. The Bazaar, which is cautious and concerned with continuity of trade, did not see in them a direct attack on its survival.

Over the years, the Islamic Republic had also eroded the Bazaar’s autonomy, tying parts of it into the state patronage system.

Without a general strike, the regime could isolate the protests. The result was a partial shift in daily practice , weaker enforcement of hijab in many areas, a visible relaxation of control , but no collapse of the state’s core structures. The movement spoke the language of rights, but it did not strike at the mechanism of revenue.

The 2025–2026 Crisis: The Return of the Tipping Point

The unrest that began in late December 2025 marked a return to the older pattern. This time, the first tremors came not from the periphery but from the Grand Bazaar in Tehran. The cause was not a single outrage but a long-building economic breakdown.

The national currency had reached a point where merchants could no longer calculate. “Loss of computational trust” describes the moment when normal economic reckoning fails.

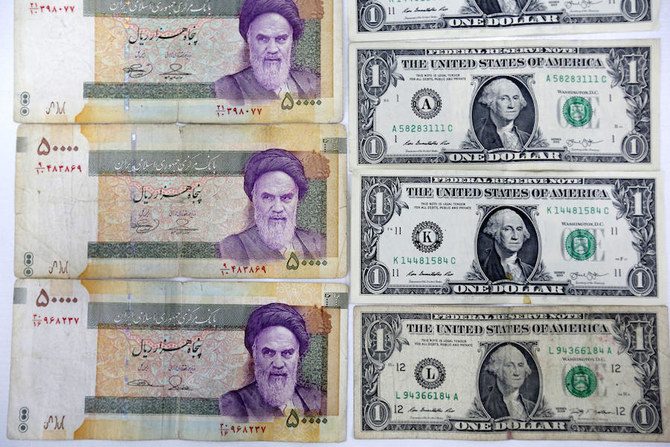

By the end of 2025, the Rial had fallen to around 1.45 million to the dollar. Under such conditions, a trader could not set a price that would cover the cost of replacing stock. Between the time of sale and the time of reordering, the currency might fall so far that the transaction became a direct loss. Selling became irrational.

The strikes of the Bazaar were not only political statements but responses to this impossibility. The new strikes were also a reaction to the budget of the Pezeshkian government, which sought higher VAT and heavier taxes on business to fund domestic security and military expansions.

Merchants saw a state trying to finance its regional ambitions and internal apparatus by draining what remained of productive life. The echo with the late Pahlavi era , oil money spent away from the traditional marketplace, was clear.

| Economic Indicator | December 2025 Status | Impact on Market Calculation |

| Exchange Rate | ~1,450,000 IRR / USD | Pricing mechanism destroyed; imports paralyzed |

| Official Inflation | 42.2% (likely understated) | Wages and fixed incomes eroded |

| Food Inflation | 72% year-on-year | Subsistence crisis among the poor |

| Tax Policy | Proposed 62% increase | Perception of predatory state extraction |

| Rial Devaluation | 40% over 2025 | Loss of faith in currency |

The Transformation of the Bazaar Under the Islamic Republic

To see why the Bazaar’s position is now more fragile than in 1979, it is necessary to trace its decline under the Islamic Republic. The Pahlavis largely left it alone, but the new order did not.

Over decades, the state created its own economic arms and favored them, cutting into the Bazaar’s role. The IRGC and the large religious foundations became the main beneficiaries of “privatization.”

Under Ahmadinejad, major state assets were shifted into their hands. They extended into construction, petrochemicals, banks, and telecommunications. They also took over much of the sanctions economy, controlling smuggling routes through key ports and airports.

Traditional merchant families had to work with or under these networks. The Bazaar ceased to be an independent power and became, in part, a subcontractor. The current strikes show the extent of the break between the Bazaar and the clergy.

The regime has increasingly blamed merchants for inflation, calling them hoarders and profiteers, while using them as tax targets. The merchants, in turn, feel abandoned and attacked by those who once presented themselves as their protectors. The trust that bound Mosque and Bazaar in 1979 has thinned.

The Regime’s Response and the Logic of Concession

The importance of the 2025–2026 unrest lies in the way it pulls together different strands of discontent. Student protests in 1999 and the Green Movement in 2009 were largely middle-class and political. The new unrest, triggered in the Bazaar, spreads across classes. Once the Bazaar is in crisis, the logic of protest alters.

When Tehran’s Grand Bazaar closed, students marched to join the merchants. Truck drivers and oil workers followed with their own actions. The state, faced with combined pressure on its economic arteries, rushed to adjust the budget, changed the Central Bank leadership, and introduced food coupons.

These responses show that uprisings in Iran become existential for the regime only when the Bazaar withdraws its cooperation and the economic gears stall.

The reaction of the Islamic Republic to the Bazaar strikes shows a degree of anxiety not visible in 2022. Khamenei tried to distinguish “legitimate” economic concern from sedition. In January 2026, Pezeshkian’s administration offered concessions that carried their own risks.

It ended a long-standing preferential exchange rate that had fed corruption among connected importers, moved toward direct subsidies for consumers, reduced the planned VAT hike, and raised pay increases closer to inflation.

The message, in effect, was that the regime could overlook the outrage of students and the demands of women longer than it could ignore the economic strike of the Bazaar. Once the merchants stopped trading, the center of the crisis moved inward, from the margins of society to the core of the system.

| Logistical Factor | 1979 Revolution | 2025–2026 Uprising |

| Communication | Cassette tapes and hey’ats | Encrypted apps and VPNs |

| Funding | Religious tithes (khoms/zakat) | Decentralized crypto and peer networks |

| Strike Coordination | Mosque networks (Mo’talefeh) | Guild-based digital chat groups |

| Regime Response | Indecisive monarchy; faltering army | Cohesive IRGC; advanced repression |

| Symbolism | 40-day mourning cycles | Hyperinflation and “Bi-Ghabliyat” |

The Marketplace as the Heart of the Storm

Writers like Ervand Abrahamian and Arang Keshavarzian have argued that the Bazaar’s behavior is a sign of elite cohesion or fracture. Revolutions do not come only from popular anger. They become possible when elites split or freeze.

In 1979, the Bazaar’s defection coincided with key military elements refusing to act. Today the IRGC is unified and heavily invested in the regime’s survival, both materially and ideologically. This is the main barrier to a repetition of 1979.

Yet the Bazaar’s involvement provides a means to weaken the regime’s resources and its claim to economic competence. If the merchants can sustain their pressure, they may contribute, over time, to wider elite divisions.

The record of 1979 and the current unrest indicates that the Bazaar remains central to Iran’s political life. Social protests like those of 2022 weaken the regime’s claim to moral authority, but they do not, by themselves, bring the system to the brink. Economic strikes by merchants do. The Bazaar provides institutional discipline, money, and cross-class links that street protests lack.

When the Grand Bazaar closes, a protest stops being a disturbance and begins to threaten the state’s survival. In the multiple crises of 2026, the return of the Bazaaris to open opposition signals a danger to the Islamic Republic greater than any since its birth.

Whether this leads to another revolutionary outcome depends on whether the Bazaar can once again connect the desires of society with the hard facts of economic life, and whether the regime can repair the broken trust that once made trade possible.