By Habib-Al Badawi

Introduction: The End of an Era

The November 2025 National Security Strategy represents the first comprehensive articulation since the Cold War’s end of an American vision that explicitly abandons ideological frameworks shaping global posture for three decades.

The document positions the United States not as the architect of “liberal order” but as a great power systematically recalibrating interests in response to a transformed landscape where “permanent American domination of the entire world” proved neither sustainable nor desirable.

This strategic realignment challenges foundational assumptions about U.S. leadership, signaling movement from diffuse global hegemony toward selective, interest-driven power projection.

The strategy rejects what it characterizes as failed post-Cold War approaches that “convinced themselves that permanent American domination of the entire world was in the best interests of our country,” arguing instead that “the affairs of other countries are our concern only if their activities directly threaten our interests.”

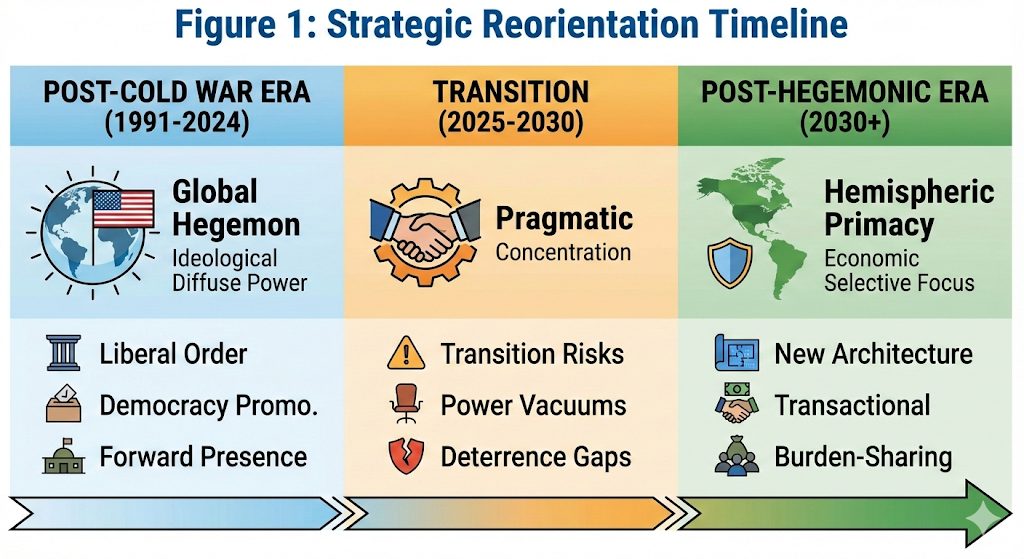

Figure 1: Strategic Reorientation Timeline

Figure 1 Caption: Strategic trajectory from post-Cold War global hegemony through transitional retrenchment toward post-hegemonic architecture. The transition period (2025-2030) presents critical vulnerabilities as American forward presence contracts before alternative leverage mechanisms mature.

The Western Hemisphere ascends to paramount strategic priority — formalized through the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine”—while traditional theaters witness a deliberate reduction in the permanent U.S. footprint (see Figure 2 below).

Allies face substantially greater burden-sharing demands, with NATO members pressed toward the “Hague Commitment” targeting five percent of GDP for defense spending.

This reflects a worldview requiring American power deployment that is sparing, efficient, and subject to rigorous cost-benefit calculations.

This constitutes neither isolationism nor conventional realism, but what the document characterizes as “pragmatic without being ‘pragmatist,’ realistic without being ‘realist,’ principled without being ‘idealistic,’ muscular without being ‘hawkish,’ and restrained without being ‘dovish.’“

More precisely, it represents synthesized doctrine anchored in economic nationalism, transactional diplomacy, and explicit prioritization of vital over peripheral interests.

This study examines the emerging strategic architecture by analyzing its internal logic, stated objectives, global implications, and potential to reshape international order.

The document’s opening assertion that American strategies since the Cold War “have been laundry lists of wishes” that “often misjudged what we should want” frames this as a fundamental course correction rather than an incremental adjustment.

Part I: Strategic Minimalism and the Reordering of Global Priorities

The Critique of Post-Cold War Strategy

The National Security Strategy opens with an explicit critique of previous American approaches, asserting they “have fallen short—they have been laundry lists of wishes or desired end states; have not clearly defined what we want but instead stated vague platitudes; and have often misjudged what we should want.”

Against this backdrop, it advances strategic minimalism as corrective: deliberate reduction in the scope of U.S. global commitments designed to conserve power for genuinely vital interests.

The strategy repositions America’s global role with striking directness. Rather than an architect of international order, it casts the United States as a great power protecting specific national interests.

The document states that “the purpose of foreign policy is the protection of core national interests” and that this “is the sole focus of this strategy.”

It continues: “After the end of the Cold War, American foreign policy elites convinced themselves that permanent American domination of the entire world was in the best interests of our country. Yet the affairs of other countries are our concern only if their activities directly threaten our interests.”

This represents a fundamental departure from the post-Cold War consensus viewing American leadership as requiring active engagement across multiple theaters simultaneously to maintain the “rules-based international order.”

The Regional Hierarchy

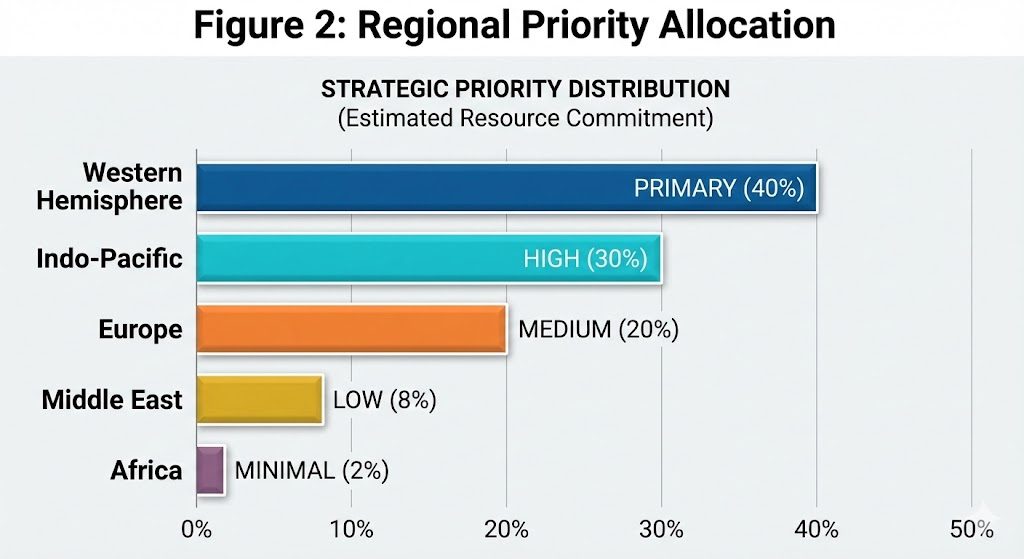

The document operationalizes minimalism through the establishment of a clear regional hierarchy, as illustrated in Figure 2. The Western Hemisphere ascends to unambiguous primacy, with the strategy declaring that “after years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere” through the “Trump Corollary.”

Figure 2: Regional Priority Allocation

Figure 2 Caption: Estimated allocation of strategic resources, diplomatic attention, and military presence across regions. The 4:3:2 ratio between Western Hemisphere, Indo-Pacific, and Europe marks a dramatic departure from post-Cold War patterns that distributed resources more evenly across theaters. Africa’s peripheral status (2%) reflects explicit deprioritization.

As Figure 2 demonstrates, the Indo-Pacific, Europe, and the Middle East receive continued attention, but with explicit expectations that allies bear substantially greater burden-sharing responsibilities.

The strategy acknowledges “a readjustment of our global military presence to address urgent threats in our Hemisphere, especially the missions identified in this strategy, and away from theaters whose relative import to American national security has declined in recent decades or years.”

This reordering creates power vacuums in regions relying on American security guarantees for decades, forcing European and Asian allies to confront substantially more autonomous defense postures.

Where previous strategies emphasized regional transformation through democracy promotion and institution-building, this framework adopts “flexible realism,” seeking “good relations and peaceful commercial relations with the nations of the world without imposing” systemic change.

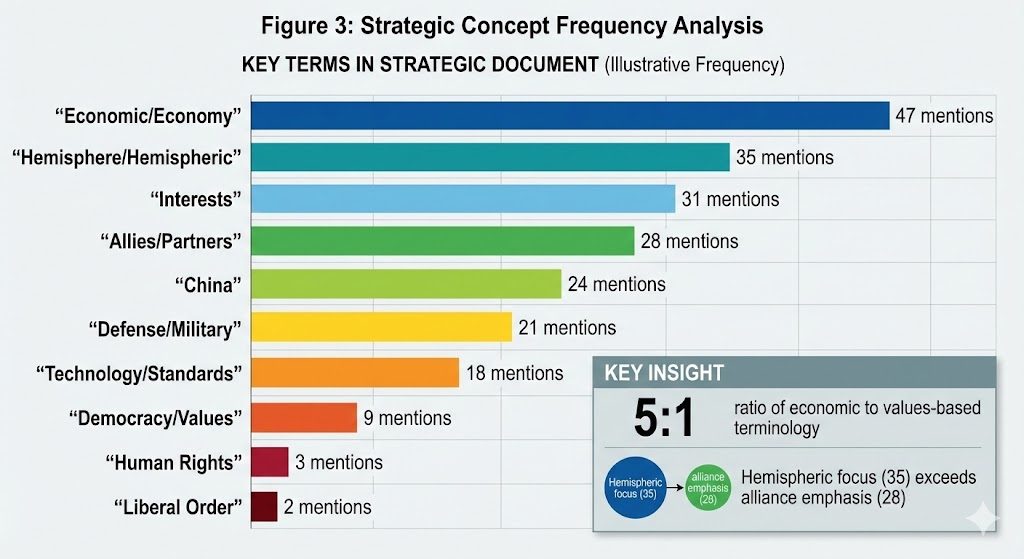

Figure 3: Strategic Concept Frequency Analysis

Figure 3 Caption: Term frequency analysis reveals the strategy’s conceptual priorities. Economic terminology dominates (47 mentions), while traditional values-based language appears sparingly. The hemispheric emphasis (35 mentions) surpassing alliance references (28) underscores geographic reorientation. This represents a quantifiable shift from ideological to material foundations of strategy.

The strategy’s call for military readjustment “away from theaters whose relative import to American national security has declined” represents more than resource reallocation—it constitutes formal acknowledgment that American power must be concentrated where it achieves maximum effect rather than diffused across commitments of varying relevance to core interests.

Figure 3 above quantifies this reorientation through term frequency analysis, demonstrating the strategy’s overwhelming emphasis on economic rather than ideological concepts.

Part II: The Western Hemisphere as Strategic Center—The Trump Corollary

Hemispheric Preeminence as an Existential Requirement

The most consequential geographic reorientation elevates the Western Hemisphere to paramount strategic priority, formalized through the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine.”

This represents more than a rhetorical gesture—it constitutes a formal declaration of strategic contraction from global to hemispheric hegemon.

The strategy states, “After years of neglect, the United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere and to protect our homeland and our access to key geographies throughout the region.”

The document frames hemispheric preeminence as an existential requirement, declaring that “the United States must be preeminent in the Western Hemisphere as a condition of our security and prosperity.”

This assertion of sphere-of-influence politics identifies specific objectives: ensuring “that the Western Hemisphere remains reasonably stable and well-governed enough to prevent and discourage mass migration to the United States,” securing “a Hemisphere whose governments cooperate with us against narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations,” maintaining “a Hemisphere that remains free of hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets,” and ensuring “our continued access to key strategic locations.”

Enforcement Mechanisms

The Trump Corollary establishes concrete enforcement mechanisms. The strategy stipulates that “we will deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets, in our Hemisphere,” and specifies that “the terms of our alliances, and the terms upon which we provide any kind of aid, must be contingent on winding down adversarial outside influence—from control of military installations, ports, and key infrastructure to the purchase of strategic assets broadly defined.”

This conditionality transforms hemispheric relationships from partnership frameworks toward patron-client dynamics, where access to American markets, security cooperation, and diplomatic support become contingent on alignment with Washington’s definition of acceptable external relationships.

Operational Framework: “Enlist and Expand”

The strategy operationalizes hemispheric primacy through “Enlist and Expand.” Under enlistment, American policy “focus[es] on enlisting regional champions that can help create tolerable stability in the region, even beyond those partners’ borders,” tasking nations to “help us stop illegal and destabilizing migration, neutralize cartels, near-shore manufacturing, and develop local private economies.”

The expansion dimension aims to “cultivate and strengthen new partners while bolstering our own nation’s appeal as the Hemisphere’s economic and security partner of choice.”

The document emphasizes commercial statecraft: “Every U.S. official working in or on the region must be up to speed on the full picture of detrimental outside influence while simultaneously applying pressure and offering incentives to partner countries to protect our Hemisphere.”

Military dimensions receive detailed specification: “readjustment of our global military presence to address urgent threats in our Hemisphere,” “a more suitable Coast Guard and Navy presence to control sea lanes,” “targeted deployments to secure the border and defeat cartels, including the necessary use of lethal force,” and “establishing or expanding access in strategically important locations.”

Confronting Chinese Presence

The strategy’s treatment of Chinese regional presence demonstrates operational directness. The document states that “non-hemispheric competitors have made major inroads into our hemisphere, both to disadvantage us economically in the present and in ways that may harm us strategically in the future,” characterizing acceptance of this presence as “another great American strategic mistake of recent decades.”

The strategy directs comprehensive action to reverse this presence, noting that the United States has “achieved success in rolling back outside influence” by demonstrating “how many hidden costs—in espionage, cybersecurity, debt traps, and other ways—are embedded in allegedly ‘low cost’ foreign assistance.”

It commits to “accelerate these efforts, including by utilizing U.S. leverage in finance and technology to induce countries to reject such assistance.”

Commercial dimensions receive equal emphasis: “Successfully protecting our Hemisphere also requires closer collaboration between the U.S. Government and the American private sector.”

The document mandates that “all our embassies must be aware of major business opportunities in their country, especially major government contracts,” and that “every U.S. government official that interacts with these countries should understand that part of their job is to help American companies compete and succeed.”

Most remarkably, it states that “the terms of our agreements, especially with those countries that depend on us most and therefore over which we have the most leverage, must be sole-source contracts for our companies.”

This hemispheric focus fundamentally reorients American strategic geography, treating the Western Hemisphere not as one region among many but as the foundational sphere upon which all other strategic calculations depend.

Part III: From Hegemony to Hierarchy—The New Architecture of American Interests

The Three-Tier Interest Framework

The overarching conceptual innovation lies in the systematic replacement of hegemonic aspirations with explicitly hierarchical frameworks. The document rejects the “costly and diffuse project” of maintaining global preeminence in favor of a clear, interest-based ranking of commitments.

This hierarchical architecture operates across two dimensions—a hierarchy of interests determining resource allocation and a hierarchy of relationships governing alliance management.

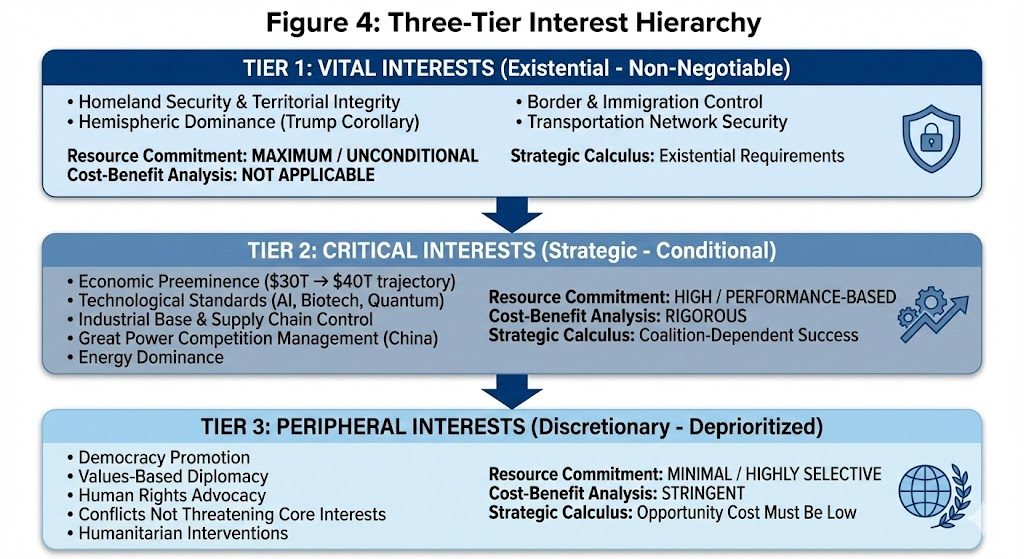

Figure 4: Three-Tier Interest Hierarchy

Figure 4 Caption: The three-tier framework establishes explicit prioritization unprecedented in post-Cold War strategy documents. Note the inversed relationship between commitment level and scope: Tier 1 receives maximum resources for narrowly defined objectives, while Tier 3’s broad aspirations receive minimal allocation. This architecture formalizes strategic triage, abandoning the pretense that all interests merit equal attention.

At the apex stand vital interests, encompassing homeland security and hemispheric dominance (see Figure 4, Tier 1).

This tier includes ensuring “the continued survival and safety of the United States as an independent, sovereign republic,” maintaining “full control over our borders, over our immigration system, and over transportation networks,” and achieving the hemispheric preeminence articulated through the Trump Corollary.

These interests receive unqualified commitment—they are not subject to cost-benefit calculation but treated as existential requirements.

The second tier comprises critical interests, centering on economic security, technological dominance, and great-power competition management (Figure 4, Tier 2).

The strategy articulates these through maintaining “the world’s strongest, most dynamic, most innovative, and most advanced economy,” preserving “the world’s most robust industrial base,” achieving “energy dominance,” and ensuring “that U.S. technology and U.S. standards—particularly in AI, biotech, and quantum computing—drive the world forward.”

Critically, the strategy frames competition with China primarily in economic rather than ideological terms, stating that policy “is not grounded in traditional, political ideology” and committing to seek “good relations and peaceful commercial relations with the nations of the world without imposing on them democratic or other social change.”

The third tier consists of peripheral interests—concerns that, while not irrelevant, they no longer command resources they once received (Figure 4, Tier 3). These include democracy promotion, ideological competition, and management of conflicts not directly threatening core American interests.

The document states it will not pursue “spreading liberal ideology” or “hectoring” nations “into abandoning their traditions and historic forms of government,” particularly referencing Middle East monarchies. It declares, “We seek good relations with countries whose systems of government differ from our own.”

The Transactional Alliance Framework

The hierarchy of relationships proves equally transformative. The strategy explicitly abandons the conception of allies as partners in shared international order-building, instead assessing relationships through contribution to specifically defined American priorities.

The document directs European allies to assume “primary responsibility for their regions,” stating that “we count among our many allies and partners dozens of wealthy, sophisticated nations that must assume primary responsibility for their regions and contribute far more to our collective defense.”

This expectation receives concrete specification through the “Hague Commitment,” establishing “a new global standard” that “pledges NATO countries to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense.” The strategy frames this not as an aspiration but as a requirement that “our NATO allies have endorsed and must now meet.”

Conditionality extends beyond defense spending. The document states, “The United States will stand ready to help—potentially through more favorable treatment on commercial matters, technology sharing, and defense procurement—those countries that willingly take more responsibility for security in their neighborhoods and align their export controls with ours.”

This formulation makes explicit that American support operates as a reward for alignment rather than an automatic function of alliance membership.

The strategy’s treatment of non-democratic partners demonstrates depth of values disengagement. It commits to seeking “good relations and peaceful commercial relations with the nations of the world without imposing on them democratic or other social change that differs widely from their traditions and histories.”

Discussing Middle East policy, it commits to “dropping America’s misguided experiment with hectoring these nations—especially the Gulf monarchies—into abandoning their traditions and historic forms of government,” arguing instead for “accepting the region, its leaders, and its nations as they are while working together on areas of common interest.”

The Central Contradiction: Coalition-Building Through Coercion

The hierarchical framework contains inherent tension potentially decisive for strategic outcomes. The document explicitly acknowledges that the United States requires coalition-scale economic cooperation to compete effectively with China, noting that American allies “together add another $35 trillion in economic power to our own $30 trillion national economy (together constituting more than half the world economy).”

It recognizes that “since the Chinese economy reopened to the world in 1979, commercial relations between our two countries have been and remain fundamentally unbalanced,” and that “the tariff approach that began in 2017” proved insufficient because “China adapted to the shift in U.S. tariff policy… in part by strengthening its hold on supply chains.”

Yet simultaneously, the strategy pursues economic nationalism through aggressive tariffs and conditional trade relationships, risking alienation of partners whose cooperation it acknowledges as essential.

The document commits to “prioritize rebalancing our trade relations, reducing trade deficits, opposing barriers to our exports, and ending dumping and other anti-competitive practices,” stating that “our priorities must and will be our own workers, our own industries, and our own national security.”

This tension represents more than tactical inconsistency—it embodies fundamental uncertainty about whether American power in the post-hegemonic era can be effectively mobilized through transactional relationships alone, or whether sustained coalition management requires deeper institutional and ideological bonds that this strategy explicitly rejects.

Part IV: Economic Statecraft as Foundation of Power

Economics as Strategic Foundation

The National Security Strategy fundamentally reconceptualizes national power by positioning economics not as a supporting element but as geostrategy’s foundation.

The document states that “economic security is fundamental to national security,” elevating industrial capacity, supply chain control, and technological standards-setting from auxiliary concerns to core elements of strategic competition.

This reflects the assessment that sustainable American power derives less from forward military presence or alliance networks than from economic depth, technological leadership, and control of critical production systems.

The Instruments of Economic Competition

The strategy articulates economic competition through interconnected dimensions. It commits to “prioritize rebalancing our trade relations, reducing trade deficits, opposing barriers to our exports, and ending dumping and other anti-competitive practices that hurt American industries and workers,” framing this not as protectionism but as correction of structural imbalances.

The strategy employs “tariffs and reciprocal trade agreements as powerful tools,” maintaining that “our priorities must and will be our own workers, our own industries, and our own national security.”

Coalition-building for economic competition receives significant emphasis. The document acknowledges that achieving scale advantages against China requires coordinated action: “The United States must work with our treaty allies and partners—who together add another $35 trillion in economic power to our own $30 trillion national economy (together constituting more than half the world economy)—to counteract predatory economic practices and use our combined economic power to help safeguard our prime position in the world economy.”

Commercial statecraft emerges as a central operational concept. The document directs that “successfully protecting our Hemisphere also requires closer collaboration between the U.S. Government and the American private sector,” mandating that “all our embassies must be aware of major business opportunities in their country, especially major government contracts.”

It continues: “Every U.S. government official that interacts with these countries should understand that part of their job is to help American companies compete and succeed.”

Standards dominance constitutes the strategy’s most forward-looking economic dimension. The document commits to ensuring “that U.S. technology and U.S. standards—particularly in AI, biotech, and quantum computing—drive the world forward,” recognizing that control of technological standards translates into sustained competitive advantage extending beyond immediate market share.

It references President Trump’s May 2025 state visits to Persian Gulf countries, where “the President won the Gulf States’ support for America’s superior AI technology, deepening our partnerships,” as a model for technology-centered partnership frameworks.

Foundational Economic Capacities

The strategy identifies several foundational capacities as prerequisites for sustained competition.

Comprehensive reindustrialization leads to: “The United States will reindustrialize its economy, ‘re-shore’industrial production, and encourage and attract investment in our economy and our workforce, with a focus on the critical and emerging technology sectors that will define the future.”

Defense industrial base revitalization receives particular emphasis: “A strong, capable military cannot exist without a strong, capable defense industrial base.”

The document acknowledges sobering lessons: “The huge gap, demonstrated in recent conflicts, between low-cost drones and missiles versus the expensive systems required to defend against them has laid bare our need to change and adapt.”

It calls for “a national mobilization to innovate powerful defenses at low cost, to produce the most capable and modern systems and munitions at scale, and to re-shore our defense industrial supply chains.”

Energy dominance emerges as both an economic priority and a strategic enabler. The strategy declares that “restoring American energy dominance (in oil, gas, coal, and nuclear) and reshoring the necessary key energy components is a top strategic priority,” arguing that “cheap and abundant energy will produce well-paying jobs in the United States, reduce costs for American consumers and businesses, fuel reindustrialization, and help maintain our advantage in cutting-edge technologies such as AI.”

Supply chain sovereignty constitutes another foundational priority. Invoking Alexander Hamilton, the strategy argues that “the United States must never be dependent on any outside power for core components—from raw materials to parts to finished products—necessary to the nation’s defense or economy.”

It commits to “re-secure our own independent and reliable access to the goods we need to defend ourselves and preserve our way of life.”

Implementation Challenges

The underlying strategic logic proves coherent: hemispheric consolidation creates a secure production sphere protecting critical supply chains; industrial capacity functions as strategic depth; technological standards control translates into sustained competitive advantages; and financial dominance provides leverage over partners. However, implementation constraints prove substantial.

The fundamental tension between demanding defense burden-sharing from allies while employing tariffs risks undermining trust when coalition-scale economic cooperation is acknowledged as essential. The strategy provides no clear mechanism for resolving this contradiction between coalition-building imperatives and unilateral economic nationalism.

Capacity bottlenecks may delay promised reindustrialization. The document acknowledges that achieving rapid defense industrial mobilization faces significant obstacles, requiring not just financial investment but also labor supply, navigating permitting challenges, and managing capital expenditure cycles.

The strategy provides limited specificity about how these bottlenecks will be overcome or what timelines are realistic.

Hemispheric economic integration faces its own challenges. Conditioning aid and market access on winding down Chinese infrastructure presence invites nationalist pushback and competitive bids by China offering better financial terms.

The strategy’s direction that agreements with dependent countries “must be sole-source contracts for our companies” may generate precisely the resistance that undermines commercial statecraft objectives.

Part V: Post-Ideological Pragmatism—Competition Without Crusade

Defining Post-Ideological Engagement

The National Security Strategy undertakes systematic disengagement from values-based foreign policy frameworks characterizing American grand strategy since at least World War II.

The document explicitly rejects what it characterizes as failed ideological projects of the post-Cold War era, declaring that policy “is not grounded in traditional, political ideology” but rather “motivated above all by what works for America—or, in two words, ‘America First.’“

The strategy articulates its post-ideological stance through “flexible realism,” defined as ensuring that “U.S. policy will be realistic about what is possible and desirable to seek in its dealings with other nations.”

It commits to seeking “good relations and peaceful commercial relations with the nations of the world without imposing on them democratic or other social change that differs widely from their traditions and histories.”

It continues: “We recognize and affirm that there is nothing inconsistent or hypocritical in acting according to such a realistic assessment or in maintaining good relations with countries whose governing systems and societies differ from ours.”

This flexible realism manifests most clearly in Middle East policy. The document commits to “dropping America’s misguided experiment with hectoring these nations—especially the Gulf monarchies—into abandoning their traditions and historic forms of government,” arguing instead for “accepting the region, its leaders, and its nations as they are while working together on areas of common interest.”

The document grounds this approach in “predisposition to non-interventionism,” invoking the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that nations are entitled to “a separate and equal station” under “the laws of nature and nature’s God.”

While acknowledging that “for a country whose interests are as numerous and diverse as ours, rigid adherence to non-interventionism is not possible,” the strategy asserts that “this predisposition should set a high bar for what constitutes a justified intervention.”

The “primacy of nations” principle reinforces this framework, declaring that “the world’s fundamental political unit is and will remain the nation-state” and asserting that “it is natural and just that all nations put their interests first and guard their sovereignty.”

The strategy commits that “the United States will put our own interests first and, in our relations with other nations, encourage them to prioritize their own interests as well.”

China Policy: From Ideological Competition to Economic Management

The strategy’s treatment of China demonstrates operational implications of post-ideological pragmatism. Unlike previous National Security Strategies framing competition through authoritarianism versus democracy lenses, this document treats China primarily as an economic competitor to be managed.

The strategy acknowledges that “President Trump single-handedly reversed more than three decades of mistaken American assumptions about China: namely, that by opening our markets to China, encouraging American business to invest in China, and outsourcing our manufacturing to China, we would facilitate China’s entry into the so-called ‘rules-based international order.’“

It continues: “This did not happen. China got rich and powerful and used its wealth and power to its considerable advantage.”

Rather than framing this as an ideological confrontation, the strategy treats it as a problem of economic competition requiring different tools. Policy toward China centers on “rebalancing America’s economic relationship with China, prioritizing reciprocity and fairness to restore American economic independence,” with trade relationships “balanced and focused on non-sensitive factors.”

The strategy frames ultimate stakes explicitly: “Our ultimate goal is to lay the foundation for long-term economic vitality,” aiming to maintain growth trajectory “from our present $30 trillion economy in 2025 to $40 trillion in the 2030s, putting our country in an enviable position to maintain our status as the world’s leading economy.”

Most remarkably, the strategy avoids characterizing competition with China through values frameworks. There is no reference to democracy versus authoritarianism, no invocation of universal values or human rights concerns, and no framing of competition as a battle between fundamentally incompatible political systems. Instead, the document focuses on measurable economic interests—market access, supply chain control, technological standards, and industrial capacity.

Deterrence Through Superiority, Preferably

The strategy’s approach to military deterrence reflects similar pragmatic calculation. Discussing Taiwan, the document states that “deterring a conflict over Taiwan, ideally by preserving military overmatch, is a priority.”

The qualifier “ideally” proves significant, suggesting recognition that overwhelming military dominance cannot be assured and that deterrence may increasingly depend on other mechanisms.

Similarly, the strategy notes that “our allies must step up and spend—and more importantly do—much more for collective defense,” warning that without substantially increased allied contributions, there could emerge “a balance of forces so unfavorable to us as to make defending that island impossible.”

This represents a departure from decades of American strategic assumption that military superiority could and would be maintained across all potential theaters. The strategy introduces selective deterrence, acknowledging that maintaining favorable military balances requires unprecedented, allied burden-sharing and that American military presence will be concentrated in highest-priority theaters rather than diffused globally.

Strategic Trade-offs

The strategic upsides of post-ideological pragmatism prove straightforward. Abandoning ideological commitments and reducing interventionist impulses frees substantial bandwidth for domestic investment and focused competition in most consequential domains. “Pragmatic” engagement “without imposing… democratic or other social change” potentially reduces friction with partners uncomfortable with American values promotion.

Eliminating open-ended commitments reduces the risk of strategic overextension. However, strategic costs prove equally consequential. Transactional relationships lacking ideological foundations may prove brittle under stress, as partners calculate interests opportunistically rather than maintain commitments based on shared values.

The erosion of American soft power—historically, a significant force multiplier—may make mobilizing international support substantially more difficult for initiatives requiring collective action.

The document itself acknowledges the importance of soft power, noting among American assets “unmatched ‘soft power’ and cultural influence,” yet simultaneously abandons many values-based appeals that have historically constituted that influence.

Perhaps most significantly, the normative vacuum created by American values disengagement may enable authoritarian consolidation in regions where American influence has historically supported liberalizing trends.

The strategy’s explicit commitment to end “hectoring” of authoritarian partners and to accept “the region, its leaders, and its nations as they are” removes what limited constraints American pressure previously imposed on illiberal governance practices.

The fundamental tension within post-ideological pragmatism lies in its assumption that material interests alone provide a sufficient basis for sustained coalition management.

Historically, democracies have demonstrated willingness to bear substantial costs for alliance commitments partly because shared political values created psychological bonds that survived periodic disagreements.

Whether transactional clarity and material inducements can substitute for these deeper ties during moments of crisis remains the strategy’s most significant untested proposition.

Part VI: Strategic Contradictions and Management Imperatives

Five Core Contradictions

The National Security Strategy’s internal logic demonstrates coherence, but its implementation environment contains contradictions—some apparently intentional, others consequential byproducts of competing imperatives.

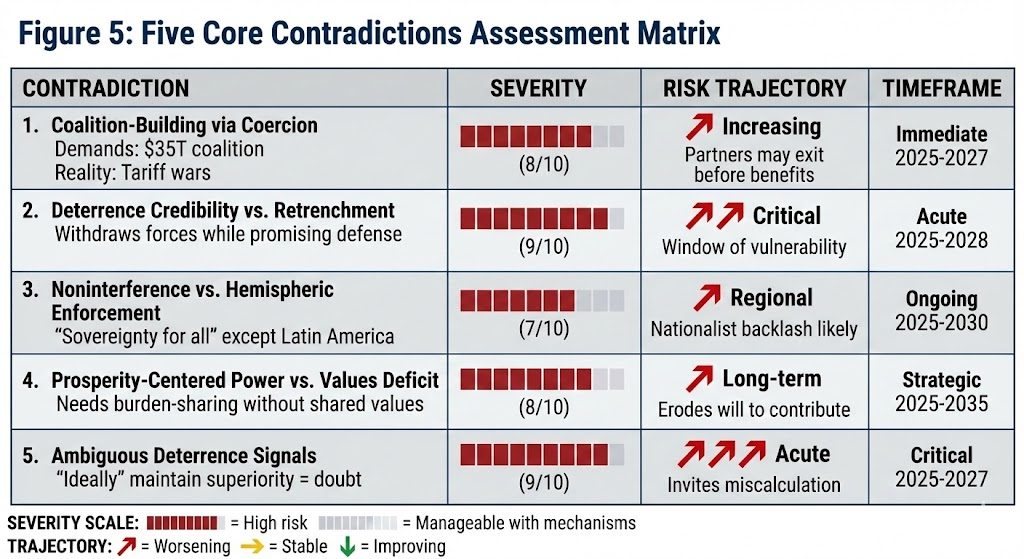

These tensions will determine whether post-hegemonic American power proves durable or whether internal inconsistencies generate strategic self-sabotage, as visualized in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5: Five Core Contradictions Assessment Matrix

Figure 5 Caption: The contradiction matrix assesses each strategic tension’s severity, risk trajectory, and critical timeframe. Contradictions #2 and #5 (both 9/10 severity) pose immediate threats to deterrence credibility during the 2025-2028 transition period when American forward presence contracts. Contradiction #1 (8/10) undermines the coalition-building essential for economic competition with China. The matrix reveals that four of five contradictions worsen over time without active management mechanisms.

First: Coalition-Building Versus Coercive Methods

As Figure 5 illustrates, this contradiction rates 8/10 in severity with an increasing risk trajectory. The strategy explicitly acknowledges that effective economic competition with China requires coalition-scale cooperation, noting that American allies “together add another $35 trillion in economic power to our own $30 trillion national economy (together constituting more than half the world economy).”

It recognizes that “the tariff approach that began in 2017” achieved limited success because “China adapted… in part by strengthening its hold on supply chains,” necessitating coordinated action among market-democratic economies.

Yet simultaneously, the strategy pursues aggressive unilateral trade policies, including tariffs against these same partners, demands they accept that “America’s current account deficit is unsustainable,” and conditions cooperation on meeting burden-sharing requirements many will find politically difficult.

Partners may reasonably conclude that alignment costs outweigh benefits, particularly when Chinese alternatives offer attractive terms without political conditionality.

Second: Deterrence Credibility Versus Strategic Retrenchment

This contradiction achieves the highest severity rating (9/10) with a critical risk trajectory (see Figure 5). The strategy commits to “readjustment of our global military presence to address urgent threats in our Hemisphere… and away from theaters whose relative importance to American national security has declined in recent decades or years.”

This retrenchment aims to concentrate resources where they matter most. However, adversaries fill power vacuums faster than industrial capacity rebuilds.

The document acknowledges that without substantially increased allied burden-sharing, “a balance of forces so unfavorable to us as to make defending that island impossible” could emerge regarding Taiwan.

This creates windows of vulnerability during transition periods when the United States has withdrawn from certain commitments but has not yet developed alternative sources of leverage.

Third: Noninterference Principle Versus Hemispheric Enforcement

Rating 7/10 in severity, this contradiction exposes geographic selectivity in the strategy’s principles. The strategy embraces “predisposition to non-interventionism” and “flexible realism,” committing to respect sovereignty and avoid imposing “democratic or other social change that differs widely from their traditions and histories.”

It declares that “all nations are entitled by ‘the laws of nature and nature’s God’ to a ‘separate and equal station’ with respect to one another.” Yet simultaneously, enforcement of hemispheric primacy requires extraordinarily intrusive terms.

The strategy states that “the terms of our alliances, and the terms upon which we provide any kind of aid, must be contingent on winding down adversarial outside influence—from control of military installations, ports, and key infrastructure to the purchase of broadly defined strategic assets.”

It continues that agreements with dependent countries “must be sole-source contracts for our companies.” These actions will inevitably be characterized as interference by Latin American governments and publics, exposing the selectivity of noninterference rhetoric that applies globally but not regionally.

Fourth: Prosperity-Centered Power Versus Values Deficit

With 8/10 severity and long-term trajectory, this contradiction strikes at coalition psychology. The strategy operates on the premise that economic vitality constitutes the foundation of sustainable power, stating that “economic security is fundamental to national security” and that maintaining economic preeminence provides “the bedrock of our global position and the necessary foundation of our military.”

However, historical democracies have tolerated significant costs in defense of alliance commitments precisely because shared ideological frameworks created willingness to bear burdens that pure material calculations might not justify.

By explicitly abandoning values-based appeals and embracing transactional frameworks, the strategy risks undermining psychological foundations enabling burden-sharing.

This proves particularly acute in Europe, where publics may increasingly question why they should assume greater defense responsibilities for a United States that no longer champions their political systems or provides extended deterrence guarantees justifying decades of defense dependence.

Fifth: Ambiguous Deterrence Signals Versus Clarity Requirements

This contradiction also rates severity 9/10 with acute near-term risks (Figure 5). The strategy frames Taiwan deterrence as achievable “ideally by preserving military overmatch,” introducing meaningful ambiguity about whether superiority can be maintained.

It warns allies that without substantially greater contributions, “a balance of forces so unfavorable to us as to make defending that island impossible” could emerge.

These formulations aim to pressure allies toward increased defense spending by signaling that American commitment is conditional.

However, they simultaneously risk emboldening adversaries who may perceive windows of opportunity during which American will or capability to intervene appears uncertain.

The strategy’s acknowledgment that maintaining favorable military balances requires conditions that may not materialize creates precisely the ambiguity that can invite miscalculation.

Management Mechanisms: From Principles to Practice

Managing these contradictions requires translating broad principles into operational mechanisms that reconcile competing imperatives. Without such mechanisms, the contradictions identified in Figure 5 will compound, potentially leading to strategic failure.

Aligning Incentives Rather Than Issuing Demands

Mechanizing burden-sharing through arrangements creating mutual benefit rather than one-sided impositions might include co-production arrangements for defense systems providing partners with industrial capacity while meeting American requirements, revenue-sharing frameworks for critical mineral development creating joint stakes in supply chain resilience, and joint standards development initiatives distributing benefits of technological leadership.

The strategy gestures toward such approaches when it states that “the United States will stand ready to help—potentially through more favorable treatment on commercial matters, technology sharing, and defense procurement—those countries that willingly take more responsibility for security in their neighborhoods.”

However, translating this principle into concrete frameworks that partners find sufficiently attractive to justify the political costs of alignment remains underdeveloped.

Sequencing Retrenchment with Capacity Building

Rather than withdrawing presence before industrial capacity reaches necessary levels, the strategy might phase drawdowns based on verified achievement of capacity benchmarks in defense-industrial surge capability, supply chain resilience, and technological dominance.

The document acknowledges that “to realize President Trump’s vision of peace through strength, we must do so quickly” in rebuilding the defense industrial base.

However, the strategy provides no timeline for when sufficient capacity will exist to justify reduced “forward presence”, nor mechanisms for determining when retrenchment can safely proceed.

Codifying Hemispheric Investment Compacts

Rather than imposing unilateral demands for winding down Chinese infrastructure presence, the United States might offer comprehensive financing packages with clearly specified governance standards, embedded regional equity stakes providing Latin American partners with ownership interests, and transparent dispute resolution mechanisms.

The strategy notes that “many governments are not ideologically aligned with foreign powers but are instead attracted to doing business with them for other reasons, including low costs and fewer regulatory hurdles,” suggesting that competitive offerings addressing partners’ legitimate economic interests might prove more effective than coercive demands.

Rebuilding Minimal Values Frameworks

The strategy need not embrace comprehensive democracy promotion to maintain baseline commitments to rule of law, anti-corruption standards, and market openness—thin but functional norms stabilizing commercial relationships without appearing as cultural imperialism.

These minimal standards might be framed not as universal values requiring global acceptance but as practical requirements for sustained economic engagement.

The document’s emphasis on “competence and merit” as “among our greatest civilizational advantages” suggests a possible foundation, though it provides no specification of how minimal standards might be articulated.

Clarifying Deterrence Thresholds

Rather than maintaining strategic opacity about conditions under which the United States would intervene, the strategy might specify capability requirements that allies must meet, timelines for achieving necessary force levels, and clear articulation of how burden-sharing affects American commitment credibility.

The document’s reference to the “Hague Commitment” setting five percent GDP defense spending targets suggests movement toward such clarity, though it provides no specification of how spending translates into capabilities or what consequences follow from failure to meet targets.

Part VII: Regional Implications and Strategic Trajectories

Western Hemisphere: Comprehensive Sphere-of-Influence Assertion

The Western Hemisphere emerges as the strategy’s geographic centerpiece, receiving primary priority allocation as shown in Figure 2 (40% of resources).

The Trump Corollary establishes hemispheric domination as an existential requirement, with strategic focus on migration control through regional stabilization, cartel disruption employing “where necessary the use of lethal force,” comprehensive asset screening to prevent adversarial acquisition of strategic infrastructure, and enforcement of conditional aid frameworks designed to systematically unwind non-American presence.

Primary risks prove substantial. Sovereignty conflicts appear inevitable as Latin American governments respond to what will be characterized as American interference, particularly given the direction that agreements “must be sole-source contracts for our companies.”

Populist backlash may be amplified by nationalist leaders framing cooperation as submission. Competition from Chinese financing offering more attractive terms without political conditions presents an ongoing challenge.

The path forward requires offering credible alternatives addressing legitimate economic interests. This necessitates equity co-finance arrangements providing genuine ownership stakes, port modernization programs enhancing regional connectivity, and supply chain integration creating shared prosperity.

Success depends on whether the United States can demonstrate that alignment delivers tangible economic benefits exceeding available alternatives.

Indo-Pacific: Economic Competition with Qualified Military Commitment

The Indo-Pacific strategy centers on “winning the economic future and preventing military confrontation,” framing competition with China primarily through economic rather than military lenses.

Receiving 30% of strategic priority allocation (Figure 2), this theater emphasizes freedom of navigation in waters through which “one-third of global shipping passes annually,” allied rearmament with the imperative that “our allies must step up and spend—and more importantly do—much more for collective defense,” and economic engagement prioritizing coalition-building among the “$35 trillion in economic power” represented by American allies.

The critical risk emerges from potential misreading of deterrence commitments (see Contradiction #5 in Figure 5).

The strategy’s statement that deterring Taiwan conflict constitutes “a priority” maintained “ideally by preserving military overmatch” introduces meaningful ambiguity, while its warning that insufficient allied contribution could produce “a balance of forces so unfavorable to us as to make defending that island impossible” may be interpreted by adversaries as signaling conditional commitment.

This ambiguity aims to pressure allies toward increased defense contributions but simultaneously risks emboldening adversaries who may perceive windows of opportunity.

Necessary moves require publishing capability roadmaps with specific timelines, expanding co-production arrangements for munitions and platforms, creating interdependencies making withdrawal costly for all parties, and building visible stockpiles and forward-deployed capabilities providing concrete evidence of commitment.

Economic dimensions prove equally critical, with the strategy acknowledging that “in the long term, maintaining American economic and technological preeminence is the surest way to deter and prevent a large-scale military conflict.”

Europe: Burden-Shifting and Civilizational Critique

European policy represents perhaps the strategy’s most politically fraught dimension, combining unprecedented burden-shifting demands with extraordinary cultural criticism.

Receiving 20% priority allocation (Figure 2), strategic focus centers on NATO burden-sharing through the “Hague Commitment,” requiring five percent GDP defense spending, ending European dependence on American security guarantees, and achieving strategic stability with Russia through “expeditious cessation of hostilities in Ukraine.”

However, the strategy transcends conventional alliance management to engage in sweeping civilizational critique, asserting that “Europe’s real problems are even deeper” than military spending or economic stagnation.

The document states that “the larger issues facing Europe include activities of the European Union and other transnational bodies that undermine political liberty and sovereignty, migration policies that are transforming the continent and creating strife, censorship of free speech and suppression of political opposition, cratering birthrates, and loss of national identities and self-confidence.”

It continues: “Should present trends continue, the continent will be unrecognizable in 20 years or less. As such, it is far from obvious whether certain European countries will have economies and militaries strong enough to remain reliable allies.”

The primary risk emerges from potential alliance fragmentation precisely when coordination proves most necessary. The strategy’s harsh critique may generate resentment, reducing cooperation on Russia policy, technology standards, and economic coordination with China—domains where transatlantic alignment remains most consequential.

European publics facing criticism that they are experiencing “civilizational erasure” while simultaneously pressed to assume substantially greater defense burdens may conclude that autonomy proves preferable to alignment.

The path forward requires shifting from criticism to concrete cooperation frameworks. This might include joint air defense procurement programs providing European industrial participation, energy resilience funds supporting diversification from Russian supply, and digital standards coalitions creating shared frameworks for technology governance accommodating legitimate regulatory concerns while preventing fragmentation benefiting China.

Middle East: Selective Engagement and Values Disengagement

Middle East policy represents the strategy’s clearest articulation of post-ideological pragmatism, explicitly abandoning decades of American emphasis on political reform while maintaining selective engagement focused on core interests.

Receiving only 8% priority allocation (Figure 2), strategic focus centers on preventing adversarial domination of energy supplies, ensuring freedom of navigation through critical chokepoints including the Strait of Hormuz and Red Sea, preventing terrorism directed at American interests, and supporting Israeli security while expanding the Abraham Accords.

However, the document frames this through dramatically reduced strategic priority, asserting that “the days in which the Middle East dominated American foreign policy in both long-term planning and day-to-day execution are thankfully over.”

The strategy commits to “dropping America’s misguided experiment with hectoring these nations—especially the Gulf monarchies—into abandoning their traditions and historic forms of government,” arguing instead that “the key to successful relations with the Middle East is accepting the region, its leaders, and its nations as they are while working together on areas of common interest.”

This represents comprehensive values disengagement, effectively declaring that regime type and governance practices constitute matters of indifference provided cooperation on defined American interests continues.

Primary risks include entrenched illiberalism potentially undermining economic modernization upon which sustained partnership depends, endemic corruption distorting commercial relationships and reducing effectiveness of technology cooperation, and strategic asset capture by competitors willing to accept higher corruption costs.

The strategy’s elimination of governance conditionality removes what limited pressure existed for institutional reforms supporting long-term stability.

The necessary approach involves conditional commercial compacts structured around transparency requirements for specific transactions rather than comprehensive governance reform, targeted anti-corruption initiatives focused narrowly on commercial relationships, and customs modernization creating baseline standards enabling efficient trade.

The strategy’s emphasis on “work[ing] with Middle East partners to advance other economic interests, from securing supply chains to bolstering opportunities to develop friendly and open markets in other parts of the world such as Africa” suggests a framework viewing regional partners as enablers of American interests beyond the Middle East itself.

Africa: From Aid to Investment

African policy receives notably limited treatment, reflecting the continent’s position as a peripheral priority within the strategy’s explicit hierarchy—receiving minimal 2% allocation (Figure 2).

The document states that “for far too long, American policy in Africa has focused on providing, and later on spreading, liberal ideology,” committing instead to “look to partner with select countries” rather than pursuing comprehensive engagement.

Strategic focus emphasizes negotiating settlements to specific conflicts, including “DRC-Rwanda” and “Sudan,” preventing the emergence of new conflicts, and transitioning “from a foreign aid paradigm to an investment and growth paradigm capable of harnessing Africa’s abundant natural resources and latent economic potential.”

The strategy identifies “immediate areas for U.S. investment in Africa, with prospects for good return on investment, includ[ing] the energy sector and critical mineral development,” framing engagement primarily through resource access rather than development partnership.

The document’s commitment to “favor partnerships with capable, reliable states committed to opening their markets to U.S. goods and services” introduces the selectivity principle, effectively acknowledging limited American capacity for comprehensive continent-wide engagement.

Primary risks include resource nationalism from African governments recognizing that Chinese engagement often provides more favorable terms, competitive disadvantage when Chinese state financing can offer better pricing and fewer conditions than American private investment requires, and continued terrorism emergence in regions where minimal American presence provides insufficient intelligence collection or partner capacity building.

The path forward requires demonstrating that American investment models deliver superior long-term returns through technology transfer, capacity building, and market access that Chinese infrastructure lending does not provide.

The strategy’s emphasis on “development of U.S.-backed nuclear energy, liquid petroleum gas, and liquefied natural gas technologies” generating “profits for U.S. businesses” while advancing American interests in “the competition for critical minerals and other resources” suggests a transactional framework where African development occurs as a byproduct of American commercial success.

Conclusion: The Architecture of Post-Hegemonic Power

The November 2025 National Security Strategy marks a definitive rupture with the post-Cold War era, articulating principles of strategic minimalism, hemispheric centrality, and interest-based hierarchy that collectively outline a doctrine where American power is to be earned, prioritized, and strategically applied rather than diffusely expended across commitments of varying relevance to core interests.

The strategy advances a calculated wager: that by contracting focus to reinvigorate the sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, forcing allies toward substantially greater self-reliance through burden-sharing mechanisms including the unprecedented “Hague Commitment” to five percent GDP defense spending, and abandoning what it characterizes as failed ideological projects of previous decades, America can preserve and enhance its position for sustained competition extending across the remainder of the century.

However, strategic success depends fundamentally on resolving internal contradictions threatening to undermine stated objectives through their implementation.

As Figure 5 demonstrates, the most consequential contradictions—deterrence credibility amid retrenchment and ambiguous signaling—both rate 9/10 severity with critical near-term trajectories.

The coalition-building contradiction (8/10 severity) undermines the economic coordination explicitly acknowledged as essential for competing with China’s combined $65 trillion market-democratic coalition.

The document itself acknowledges fundamental uncertainties, noting potential for “a balance of forces so unfavorable to us as to make defending that island impossible” if allied burden-sharing does not materialize at required levels. This represents strategic humility notably absent from previous American strategy documents.

Yet this humility simultaneously signals vulnerability that adversaries may seek to exploit, creating windows of opportunity during transition periods when American forward presence recedes before alternative sources of leverage reach levels sufficient to compensate.

The strategy’s post-ideological approach embodies the fundamental wager that power derives more durably from supply chains than from sermons—from control of industrial capacity, technological standards, critical corridors, and sustained economic dynamism rather than from universal values frameworks.

This wager may prove sound—economic depth and technological leadership have historically provided foundations for sustained great power competition.

However, realizing this vision requires translating demands into genuine incentives that partners find sufficiently attractive to justify political costs of alignment, timing strategic retrenchment to avoid deterrence gaps during capacity rebuilding, and maintaining minimal institutional and normative frameworks sufficient to keep coalitions coherent under stress.

Without mechanisms for achieving these objectives, the strategy’s contradictions—coalition-building through coercion, deterrence through ambiguity, noninterference paired with hemispheric enforcement, and values disengagement while expecting sustained burden-sharing—risk eroding the very resilience and partnerships the framework seeks to construct.

The world confronts a more calculating, less predictable, and deliberately post-hegemonic United States that characterizes itself as pursuing policy that is “pragmatic without being ‘pragmatist,’ realistic without being ‘realist,’ and principled without being ‘idealistic.’“

This formulation captures the document’s systematic attempt to transcend traditional ideological categories while maintaining that American interests can be clearly identified, prioritized, and advanced through focused application of national power.

The era of automatic American leadership, sustained by combinations of forward military presence, extended deterrence guarantees, alliance institutions, and values-based appeals, has formally ended with this strategy document.

What emerges constitutes neither American decline nor conventional realism, but rather a calculated redefinition of how the United States mobilizes power when it judges that ideological projects have proven unsustainable, diffuse global presence has generated diminishing returns, and allies have systematically under-contributed to collective defense.

Whether this redefinition proves strategically sound or historically misguided depends less on the elegance of its conceptual architecture—which demonstrates considerable coherence—than on whether implementation can overcome the contradictions embedded within it.

The opening chapter of America’s post-hegemonic era has been written with unusual clarity about ends and remarkable frankness about limitations of available means.

Subsequent chapters will reveal whether strategic minimalism can coexist with sufficient global influence to protect interests the strategy itself defines as vital, whether economic coalitions can be constructed and sustained on transactional foundations when ideological bonds dissolve, whether allies accept burden-sharing demands without extended deterrence guarantees that historically justified them, and whether an America that has abandoned missionary ambitions retains the capacity to rally partners when interests demand collective action.

The architecture is visible in its hierarchies (Figure 4), its hemispheric focus (Figure 2), its economic foundations (Figure 3), and its post-ideological pragmatism (Figure 1). Its durability will be tested against the friction of international politics, where strategic logic confronts implementation constraints, where coalition management requires more than transactional clarity, and where retrenchment creates power vacuums that adversaries exploit before alternative sources of leverage materialize.

The National Security Strategy of November 2025 articulates post-hegemonic American power with conceptual sophistication. Whether that power proves sustainable depends on execution dimensions where clarity remains notably incomplete, and where the distance between strategic architecture and operational reality will ultimately determine whether this marks successful adaptation to constrained circumstances or the beginning of more profound strategic disorientation as contradictions compound and mechanisms for managing them fail to materialize.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Averitt. (2024, September 23). Redrawing the supply chain: The ultimate guide to nearshoring and reshoring. https://www.averitt.com/blog/ultimate-guide-nearshoring-reshoring

Britannica. (2014, February 20). Forward basing. https://www.britannica.com/topic/forward-basing

Britannica. (2015, August 17). Liberal internationalism. https://www.britannica.com/topic/liberal-internationalism

Britannica. (n.d.). Strait of Hormuz. Retrieved December 6, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Strait-of-Hormuz

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). (2024, October 15). Supply chain sovereignty and globalization. https://www.csis.org/analysis/supply-chain-sovereignty-and-globalization

Council on Foreign Relations. (2025). Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo [Global Conflict Tracker]. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violence-democratic-republic-congo

Dugard, J. (2023). The choice before us: International law or a ‘rules-based international order’? Leiden Journal of International Law, 36(2), 253–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S092215652200058X

E-International Relations. (2023, August 2). Beyond the narrative of China’s debt trap diplomacy. https://www.e-ir.info/2023/08/02/beyond-the-narrative-of-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy/

Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. (n.d.). Hamilton’s Report on the Subject of Manufactures, 1791. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/hamiltons-report-subject-manufactures-1791

Guiberteau Ricard, J., & Liang, X. (2025). NATO’s new spending target: Challenges and risks associated with a political signal. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. https://www.sipri.org/commentary/essay/2025/natos-new-spending-target-challenges-and-risks-associated-political-signal

National Archives. (2022, May 10). Monroe Doctrine (1823). https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/monroe-doctrine

National Archives. (n.d.). Declaration of Independence: A transcription. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

SIPRI. (2025). Military expenditure. In SIPRI Yearbook 2025: Armaments, disarmament and international security. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2025/03

SIPRI. (2025, April 28). Unprecedented rise in global military expenditure as European and Middle East spending surges [Press release]. https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2025/unprecedented-rise-global-military-expenditure-european-and-middle-east-spending-surges

SYSPRO. (2023, March 30). What is supply chain sovereignty? https://www.syspro.com/blog/supply-chain-management-and-erp/what-is-supply-chain-sovereignty-and-how-can-manufacturers-achieve-this/

The White House. (2022, February). Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States. https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf

The White House. (2025). National Security Strategy of the United States of America. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/2025-National-Security-Strategy.pdf

ThomasNet. (2025, January 15). Reshoring vs. nearshoring: Differences and similarities. https://www.thomasnet.com/insights/reshoring-vs-nearshoring/

Trachtenberg, M. (2025). The rules-based international order: A historical analysis. International Security, 50(2), 7–54. https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00511

U.S. Department of Defense. (2013). Command and control for joint maritime operations (Joint Publication 3-32). https://www.militarydictionary.org/term/forward-presence

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. (n.d.). Monroe Doctrine, 1823. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/monroe

U.S. Department of State. (2021, January 13). The Abraham Accords. https://2017-2021.state.gov/the-abraham-accords/index.html

U.S. Department of State. (2024, June 3). Indo-Pacific Strategy. https://2021-2025.state.gov/indo-pacific-strategy/

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). The Abraham Accords. https://www.state.gov/the-abraham-accords

Wikipedia. (2025, December 4). Democratic Republic of the Congo–Rwanda conflict (2022–2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Democratic_Republic_of_the_Congo–Rwanda_conflict_(2022–2025)

Wikipedia. (2025, November 28). Debt-trap diplomacy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debt-trap_diplomacy

Wikipedia. (2025, October 21). Report on Manufactures. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Report_on_Manufactures