Authored By: Prof. Habib Badawi, Mr. Ali Kassab

ABSTRACT

This study examines the December 2024 collapse of the Syrian regime as a case of intelligence-led displacement—regime change achieved through covert paralysis of command structures rather than military defeat. Within eleven days, a government that survived thirteen years of civil war ceased functioning without decisive battle, visible political rupture, or leadership defiance. Using intelligence studies methodology—pattern recognition, tradecraft signature analysis, and testimonial triangulation—we demonstrate that Syria’s collapse exhibits signatures of coordinated intelligence operations rather than organic failure.

We identify Russia’s GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate) as the probable architect (75-85% confidence), leveraging nine years of embedded access to execute synchronized paralysis across five domains: command communications, airspace operations, elite security, leadership extraction, and information environment. The operation succeeded through a tacit “alliance of silence” among major powers (Russia, Iran, Turkey, United States), each securing strategic benefits while avoiding public accountability.

This research contributes three theoretical innovations: (1) conceptualizing “silent regime change” as distinct from conventional regime change modalities; (2) revealing the “patron-as-executor paradox” whereby protection mechanisms become termination pathways; (3) documenting multilateral deconfliction through operational signals rather than diplomatic coordination. We provide vulnerability assessment frameworks for externally dependent regimes and demonstrate how intelligence services function as autonomous geopolitical actors capable of engineering state-level transformation.

Keywords: covert regime change, intelligence-led displacement, GRU operations, patron-client relations, Syrian collapse, tacit deconfliction, hybrid warfare.

- INTRODUCTION

Regimes typically collapse through visible mechanisms: military defeat, popular revolution, or internal coup. Syria’s December 2024 collapse defied these patterns. Within eleven days, a government apparatus that survived thirteen years of civil war simply ceased functioning—without decisive battles, without factional contestation, without public leadership declarations. Cities surrendered without major combat. Command structures dissolved without visible resistance. The president departed to Moscow in what intelligence assessments characterized as a “transfer of power” rather than emergency escape. Most remarkably, major powers with substantial interests in Syria’s future—Russia, Iran, Turkey, and the United States—exhibited coordinated non-intervention, neither resisting nor publicly acknowledging the regime’s termination.

This study reconstructs the operational architecture of Syria’s collapse through convergent indicator analysis, examining command paralysis, airspace operations, and elite evacuations to identify intelligence tradecraft signatures. Testimonies from field officers, synchronized silence of military channels, inexplicable withdrawal of air support, and coordinated evacuation of security elite families point to systematic engineering rather than spontaneous failure.

At the center of this silent regime change stands Russia’s military intelligence service—the GRU—whose covert capabilities extend far beyond the battlefield. For nine years, the GRU shaped Syrian operations from the shadows, controlling airspace, commanding key fronts, and embedding itself within the regime’s decision-making apparatus. When Moscow’s strategic calculus shifted, the GRU’s role transformed from guardian to executor. The collapse that followed bore hallmarks of professional intelligence-led operations: deniable, coordinated, and devastatingly effective.

Research Question and Contribution

Can intelligence services engineer regime collapse through non-kinetic means? If so, what operational signatures distinguish intelligence-led displacement from conventional regime change? We examine three dimensions: (1) operational mechanisms of intelligence-induced paralysis, (2) attribution frameworks identifying probable architects, (3) strategic logic enabling multilateral acquiescence.

Our analysis focuses on the final eleven-day operational window (November 27-December 8, 2024), contextualized within Russia’s nine-year military engagement in Syria (Trenin, 2018) and evolving patron-client dynamics between Moscow and Damascus (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991). The research deliberately examines intelligence tradecraft and covert statecraft rather than conventional military or diplomatic explanations, filling a critical gap in existing literature on Middle Eastern geopolitics and contemporary regime change.

This study makes four contributions to existing scholarships. First, it establishes “silent regime change” as a distinct theoretical category, differentiating intelligence-led displacement from military invasion, popular revolution, internal coup, or economic collapse.

Second, it advances methodological frameworks for analyzing covert operations under conditions of intentional opacity (Bennett & Checkel, 2015; Heuer, 1999), demonstrating how convergent indicator analysis generates disciplined inference despite evidentiary constraints.

Third, it reveals the “patron-as-executor paradox”—the reality that embedded access enabling regime protection simultaneously creates infrastructure for regime termination (Crawford, 2011). Fourth, it documents the “alliance of silence” phenomenon (Goddard, 2010), whereby great powers achieve convergent outcomes through tacit deconfliction rather than formal diplomatic coordination.

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- Intelligence-Led Displacement: Conceptual Foundations

The Syrian case requires integration of theoretical insights from multiple scholarly traditions: covert action theory, principal-agent dynamics, network embeddedness, and hybrid warfare. Intelligence covert action scholarship establishes operations designed to influence foreign political conditions while obscuring sponsoring government roles (Johnson, 1996; Godson, 1989; Poznansky, 2020). Covert action represents a distinctive category of statecraft, defined as operations where the sponsor’s role remains neither apparent nor publicly acknowledged.

We extend this framework by demonstrating how embedded patron access enables not just influence but active regime termination. Johnson’s (1996) framework positions covert action as the “quiet option” between diplomacy and war. The Syrian case exemplifies what Godson (1989) termed “active measures”—sustained intelligence operations designed to shape political outcomes through embedded access, technical penetration, and elite manipulation rather than conventional military force. Poznansky (2020) demonstrates how covert interventions exploit attribution complexity to reduce reputational costs, a dynamic clear where no major power claimed responsibility despite achieving preferred outcomes.

Principal-agent theory illuminates asymmetric alliance dynamics. When a patron provides essential security guarantees to a client, it gains structural leverage over the client’s decision-making autonomy (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991). The relationship between Moscow and Damascus reflects classic principal-agent dynamics: clients may pursue independent policies conflicting with patron interests (agency slack), and patrons face rising costs when clients become liabilities. Crawford’s (2011) concept of “strategic abandonment”—calculated withdrawal when a client’s utility falls below costs—partially explains Russian behavior. However, in intelligence-saturated relationships, patrons possess infrastructure not just for withdrawal but for active termination, converting accumulated access into coercive capability.

Network theory provides analytical tools for understanding embedded access. Burt’s (1992) framework demonstrates how actors positioned at critical network junctions gain disproportionate influence. The GRU’s multi-year embedding within Syrian command structures, air operations, and elite security precisely created such bridge positions—enabling both information advantage and capacity to sever connections at will (Hafner-Burton, Kahler, & Montgomery, 2009). This extends to what Nexon and Wright (2007) call “indirect institutional power”: shaping outcomes through control of connective tissue linking decision-makers, operational units, and external enablers.

Hybrid warfare theory, particularly Hoffman’s (2007) concept of “compound conflicts” and Galeotti’s (2019) “non-linear warfare,” provides essential context. The Syrian operation exemplifies orchestrated use of information operations, covert action, and strategic deception to achieve effects traditionally associated with conventional military victory. Critical to this framework is Freedman’s (2003) analysis distinguishing “brute force” from “coercive diplomacy.” The Syrian collapse represents a third category: intelligence-induced paralysis, where target resistance capacity is neutralized before confrontation, rendering traditional escalation dynamics irrelevant (Badawi, 2025).

- Integrated Theoretical Model

Synthesizing these frameworks, we propose an integrated model of intelligence-led regime displacement characterized by three phases:

PHASE 1 – PREREQUISITE CONDITIONS: Deep patron-client dependency creating embedded access, regime structural vulnerabilities (centralized command, external security reliance), and shifting patron cost-benefit calculations (Crawford, 2011; Lake, 2009).

PHASE 2 – OPERATIONAL MECHANISM: Targeted paralysis of command and control (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008), withdrawal of critical enablers (airpower, logistics), elite inoculation through preemptive evacuation (Quinlivan, 1999), managed leadership extraction (Galeotti, 2019), and multilateral deconfliction (Goddard, 2010).

PHASE 3 – OUTCOME CHARACTERISTICS: Regime collapse without decisive battle, controlled transition minimizing chaos, deniable attribution (Poznansky, 2020), preservation of patron strategic assets, and acquiescence by competing powers.

This model positions intelligence agencies as autonomous geopolitical actors capable of reshaping state structures when three conditions converge: accumulated access enabling operational leverage, strategic incentives for regime recalibration, and tacit acceptance by other consequential powers. The theoretical innovation lies in demonstrating that modern intelligence services can achieve state-level transformation through non-kinetic means, creating a new modality of power projection operating below traditional thresholds of military intervention (Hoffman, 2007; Galeotti, 2019).

- METHODOLOGY

- Research Design and Analytical Approach

This study employs multi-method intelligence studies analysis designed to reconstruct covert operations under conditions of intentional opacity. The methodology integrates four complementary analytical techniques: pattern recognition and convergent indicator analysis, tradecraft signature attribution, testimonial triangulation, and counterfactual diagnostic testing.

Pattern Recognition and Convergent Indicator Analysis: We identify operational anomalies across multiple domains—command communications, airspace operations, elite movements, and leadership security—documenting their temporal clustering within an eleven-day window. Rather than relying on isolated evidence, we establish convergent patterns where simultaneous disruptions across disconnected systems point toward centralized orchestration. Following Heuer’s (1999) structured analytic techniques, when multiple independent indicators converge toward the same hypothesis, confidence increases multiplicatively. The temporal compression of events—regime collapse across five fronts within eleven days—serves as critical discriminator, as organic processes typically exhibit gradual cascades rather than synchronized paralysis (Brownlee, 2007; Quinlivan, 1999).

Tradecraft Signature Attribution: Drawing on intelligence studies literature, we identify operational characteristics consistent with GRU covert action doctrine: non-kinetic methods, deniability architecture, exploitation of embedded access, synchronized multi-axis operations, and controlled leadership extraction (Richelson, 2007; Hughes, 2017). We apply attribution tests comparing observed signatures against alternative hypotheses (internal coup, spontaneous collapse, diplomatic coercion, other external actors), evaluating which explanation best accounts for documented phenomena.

Attribution in covert operations must rely on pattern matching and probabilistic inference rather than definitive proof, as professional intelligence services design operations to obscure origins (Hughes, 2017). We establish attribution thresholds: low confidence (30-50%), moderate confidence (50-70%), and high confidence (70-85%). Intelligence operations designed for deniability preclude absolute attribution. Our convergent indicator methodology—triangulating testimonies, operational signatures, temporal clustering, and counterfactual tests—yields high-confidence attribution (75-85%) for GRU involvement.

Testimonial Triangulation: We synthesize field officer accounts, diplomatic source reporting, and security apparatus insider testimonies, cross-referencing claims across multiple independent sources. Given self-interested nature of such testimonies, we apply critical source evaluation (Patton, 2015), privileging accounts providing specific operational details, acknowledging uncertainty, and corroborated through observable outcomes (family evacuation timing, air mission cessation, communication disruptions).

Our evidentiary basis combines three source types: (1) Primary testimonial evidence from field officers with direct operational experience (moderate-high reliability; corroborated across independent sources); (2) Observable operational indicators including documented cessation of Russian air operations, elite evacuation timing, and synchronized front collapses (high reliability; independently verifiable); (3) Strategic logic assessment inferring motivations from documented interests and outcomes (moderate reliability; compelling but not determinative). This triangulation generates cumulative confidence exceeding any single source stream.

Counterfactual Diagnostic Testing: To strengthen causal inference, we construct counterfactual scenarios for alternative explanations—diplomatic pressure only, internal military coup, opposition military victory—and test whether these alternatives would produce observed operational signatures (Fearon, 1991; Bennett & Checkel, 2015). We evaluate temporal sequencing (instantaneous versus gradual), coordination patterns (centralized versus distributed), and international responses (resistance versus acquiescence) to discriminate among competing hypotheses.

- Methodological Limitations

Three principal limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, testimonial evidence derives from sources with potential self-interest in shaping narratives, requiring critical evaluation rather than uncritical acceptance (Patton, 2015). Second, absence of internal GRU documentation means attribution must rely on external signatures and pattern recognition rather than direct confirmation (Richelson, 2007). Third, classification of intelligence materials by all relevant governments means publicly available evidence represents only partial view of operational reality.

Despite these constraints, the convergent methodology generates analytical confidence sufficient for scholarly contribution. The temporal clustering of events, consistency of operational signatures with established tradecraft, and strategic logic aligning capacity with motive collectively exceed the evidentiary threshold for advancing intelligence-led displacement as the most coherent explanation for Syria’s collapse.

- EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS: OPERATIONAL ARCHITECTURE OF COLLAPSE

- Temporal Reconstruction: The Final Eleven Days

The temporal concentration of operational disruptions provides compelling evidence for centralized orchestration rather than spontaneous collapse. Table 1 presents the chronological reconstruction demonstrating synchronized paralysis across multiple independent systems.

TABLE 1: TEMPORAL-OPERATIONAL CONVERGENCE MATRIX (FINAL 11 DAYS)

| Day | Command Disruption | Air Operations | Elite Movement | Strategic Signal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-11 | Normal flow maintained | Routine Russian support | No unusual activity | Front lines stable |

| D-10 | Initial irregularities | Sortie frequency down | — | Minor adjustments |

| D-9 | Brigade commanders report delayed orders | Reduced Aleppo coverage | — | Forward units uncertain |

| D-8 | General Staff gaps | Withdrawal accelerates | — | Defensive confusion |

| D-7 | Contradictory directives from multiple sources | Near-total cessation | — | Command coherence failing |

| D-6 | Presidential palace silent | Damascus airspace undefended | — | Units await orders that never arrive |

| D-5 | Complete paralysis reported | Zero operations | — | Multiple fronts collapse |

| D-4 | No coherent orders to field | Continued blackout | — | Minimal opposition resistance |

| D-3 | Total communication breakdown | Air cover absent | 32 FAMILIES EVACUATED | Standalone withdrawals |

| D-2 | Command structure dissolved | No capital defense support | Elite evacuation continues | ASSAD TO MOSCOW |

| D-1 | No functioning authority | Airspace ceded entirely | Final departures | Transition negotiations |

| D-DAY | Regime apparatus ceases | No regime air presence | All personnel extracted | Damascus falls unopposed |

Note: Diagnostic evidence for pre-planned coordination (72-hour advance evacuation timing).

As Table 1 demonstrates, progression from normal operational status (D-11) to complete regime apparatus dissolution (D-Day) followed systematic trajectory across five distinct domains. The simultaneity of command communication breakdown, airpower withdrawal, and elite evacuation within compressed timeframe defies conventional explanations of organic regime failure, which typically exhibit gradual cascading effects rather than synchronized paralysis (Brownlee, 2007; Quinlivan, 1999).

Particularly significant is timing of senior officer family evacuations (D-3), occurring precisely 72 hours before the capital’s fall—a degree of temporal precision suggesting advance knowledge and coordinated planning rather than reactive crisis management. The initial phase (D-11 to D-8) exhibited subtle degradation: communication irregularities, declining sortie frequencies, and growing uncertainty among forward units. This pattern suggests deliberate calibration—disrupting command efficiency without triggering immediate alarm that might provoke countermeasures or external intervention.

The middle phase (D-7 to D-5) witnessed accelerating paralysis: contradictory orders, near-total air operations cessation, and simultaneous front collapses. The terminal phase (D-4 to D-Day) completed the operational sequence: elite extraction, leadership transfer, and unopposed opposition entry into Damascus.

Figure 1. Strategic architecture of synchronized multi-domain paralysis during the Syrian regime collapse (December 2024).

- Multi-Domain Paralysis Architecture

The operation’s effectiveness derived from simultaneous action across five independent domains, creating systemic effects that overwhelmed regime capacity for adaptation. Isolated disruption in any single domain might have been overcome through organizational resilience and improvisation. Synchronized disruption across all domains simultaneously prevented compensatory responses, as each disruption compounded others’ effects.

Command and Control Domain: The Syrian regime exhibited highly centralized decision-making with all orders flowing through palace and General Staff (Quinlivan, 1999). Sudden cessation of coherent orders, contradictory directives from multiple apparent sources, and complete communication breakdown between command nodes created systemic paralysis. Officers awaited instructions that never arrived. This level of disruption required intimate knowledge of communication protocols, encryption systems, and verification procedures—knowledge accumulated through years of embedded advisory relationships rather than external penetration alone.

The intelligence tradecraft literature identifies “command disarticulation” as core component of non-kinetic operations designed to paralyze adversary decision-making (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008). By targeting the apex of the command pyramid—linkages between political leadership and military execution—external actors induce systemic paralysis cascading throughout subordinate structures. Field units retain physical combat capacity but lack coherent direction, creating conditions where non-resistance becomes rational default response.

Airspace Operations Domain: Abrupt cessation of Russian air operations occurred across all critical fronts simultaneously. Withdrawal of air cover from Damascus, Aleppo, and Idlib; no defensive air missions during final assault; complete de-tasking of ISR and strike packages. This required direct authority to suspend sortie generation—powers residing exclusively with actors controlling Syrian air operations infrastructure. Russia’s decade-long management of Syrian airspace through Hmeimim Air Base precisely provided this capability.

The strategic significance of air power in Syrian military operations cannot be overstated. Russia’s intervention in September 2015 fundamentally altered conflict trajectory by providing precision strike capabilities, close air support, and ISR dominance that compensated for Syrian Arab Army weaknesses (Trenin, 2018). Removing this force multiplier at the critical moment stripped regime forces of primary advantage, converting tactical positions into strategic vulnerabilities overnight. The psychological impact paralleled material effect: troops recognizing absence of air cover understood that external protection had been withdrawn, signaling regime abandonment at highest levels.

Elite Security Domain: Coordinated evacuation of 32 senior officer families 72 hours before collapse removed the human element of command, ensuring key personnel were psychologically and physically disengaged. Officers whose families had been safely extracted faced fundamentally altered incentive structures: resistance risked personal safety with families already secure elsewhere, while accommodation offered survival without sacrifice. This “elite inoculation” strategy—protecting potential spoilers while neutralizing their resistance capacity—represents sophisticated understanding of authoritarian regime cohesion dynamics (Quinlivan, 1999).

Quinlivan’s (1999) analysis of coup-proofing in personalist regimes demonstrates that elite loyalty depends on credible protection of family networks alongside material benefits. External actors who can guarantee family security while signaling regime termination effectively sever loyalty bonds sustaining authoritarian resilience. The Syrian case suggests this mechanism was deliberately exploited: families evacuated before collapse was publicly evident, indicating advance coordination rather than reactive flight.

Leadership Management Domain: Presidential extraction to Moscow two days before Damascus fell, characterized as “transfer” rather than emergency escape, required not only diplomatic channels for reception but capacity to neutralize factional resistance within the regime. Internal coups typically involve leader detention or elimination, not external extraction with full protocol (Powell, 2003). This pattern matches established GRU tradecraft in managing client regime transitions: preserving leadership figures under external custody prevents martyrdom dynamics while enabling future leverage (Galeotti, 2019).

Information Environment Domain: Absence of regime-end messaging, no counter-mobilization calls, and silence preventing loyalist last-stand dynamics created narrative vacuum enabling smooth transition. Authoritarian regimes under existential threat typically resort to mass mobilization rhetoric, appealing to sectarian solidarity, nationalist sentiment, or revolutionary ideology to generate last-stand resistance (Quinlivan, 1999). The absence of such messaging in Syria’s terminal phase created informational vacuum that normalized stand-down. Units awaiting orders for mobilization received only silence, which they interpreted as implicit authorization to disengage.

- Attribution Analysis: Identifying the Architect

The methodological challenge of attributing covert operations under conditions of intentional opacity requires systematic evaluation of potential actors against established criteria of capacity, motive, and operational signature compatibility. Table 2 provides structured comparative assessment.

TABLE 2: COMPARATIVE ATTRIBUTION ANALYSIS

| Actor | Capacity | Strategic Motive | Signature Match | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUSSIA (GRU) | HIGH: 9-year embedded presence, airspace control, command integration, advisory roles, evacuation protocols | STRONG: Reduce Syrian costs, curb Iranian drift, reallocate to Ukraine, retain bases (Tartus, Hmeimim) | STRONG: Non-kinetic paralysis, access-enabled disruption, controlled extraction, deniability architecture | HIGH (75-85%) |

| IRAN (TEHRAN) | MODERATE: Militia networks, intelligence presence, institutional penetration | WEAK: Benefits from continuity, collapse threatens networks, loss of strategic depth vs Israel | POOR: No airspace control, requires opposition from Russia, tacit acceptance evident | VERY LOW (5-10%) |

| TURKEY (ANKARA) | MODERATE: Regional proximity, border control, intelligence capabilities, proxy forces | MIXED: Assad removal benefits, Kurdish agenda, border security, chaos risks | PARTIAL: Could facilitate corridors, lacks command paralysis capacity, insufficient guarantees | LOW (10-20%) |

| UNITED STATES | MODERATE: Intelligence capabilities, regional presence, diplomatic leverage | MIXED: Desires removal, prefers burden-shifting, risk-averse on direct action | POOR: No attributable assets, inconsistent with non-intervention policy | VERY LOW (5-10%) |

| INTERNAL COUP | LOW-MODERATE: Security factions, officer discontent | VARIABLE: Personal survival, factional gains, alternative leadership | POOR: No factional signaling, no coup announcement, external extraction contradicts seizure | LOW (10-15%) |

| SPONTANEOUS COLLAPSE | N/A: No coordinating actor | N/A: Systemic failure without direction | VERY POOR: Simultaneous five-front collapse, synchronized evacuations, coordinated air withdrawal, managed extraction | VERY LOW (<5%) |

The attribution matrix reveals significant variance across potential actors. Russia (GRU) achieves high-confidence assessment (75-85%) based on convergent strengths across all evaluated dimensions: exceptional capacity derived from years of embedded presence, compelling strategic motives aligned with documented policy shifts (Trenin, 2018; Giles, 2019), and strong operational signature correspondence with established GRU tradecraft (Galeotti, 2019; Richelson, 2007).

The capacity dimension proves particularly diagnostic. Multi-domain paralysis requires simultaneous control over command communications, airspace operations, elite security, and international transit—a combination of capabilities possessed only by actors with deep, long-term integration into Syrian regime structures. Russia’s nine-year military engagement precisely created this infrastructure: embedded military advisors within General Staff, comprehensive control of Syrian airspace through Hmeimim Air Base, technical integration of communication and air defense systems, and diplomatic channels for managing leadership transitions (Trenin, 2018).

Strategic motive provides additional discriminatory power. Moscow’s documented frustrations with Assad’s governance by 2024—Iranian institutional overreach diluting Russian influence, regime’s economic unsustainability draining resources, Assad’s exploration of back-channels with Washington—created clear incentives for regime recalibration (Trenin, 2018; Giles, 2019). The Ukraine conflict intensified these pressures, as sustaining costly Syrian commitments competed with priority theaters. Critically, Russia could achieve strategic objectives (retaining Tartus and Hmeimim bases, curbing Iranian dominance, reducing financial burden) through regime change rather than regime preservation (Crawford, 2011; Lake, 2009).

Alternative hypotheses demonstrate critical deficiencies when subjected to rigorous counterfactual testing. Iran’s exceptionally low probability assessment (5-10%) stems primarily from strategic motive misalignment: collapse threatened rather than advanced Tehran’s institutional investments in Syrian security structures. The observable reality that Iranian assets did not mobilize for regime defense, despite possessing substantial militia networks, suggests tacit acceptance rather than authorship—a finding more consistent with deconfliction than with Iranian operational initiative.

The internal coup hypothesis warrants scrutiny given superficial plausibility. Military coups in authoritarian regimes typically exhibit specific signatures: factional contestation over media outlets, competing command directives from rival centers, public justifications by new authority, and signals to external patrons seeking recognition (Powell, 2003; Quinlivan, 1999). The Syrian case exhibited none of these characteristics. Instead, complete command silence without competing directives, zero coup announcements, and external extraction of leadership to Moscow contradict standard coup dynamics. Internal seizures aim to capture, not evacuate, heads of state.

- Counterfactual Diagnostics: Testing Alternative Explanations

Strengthening causal inference requires systematic testing of alternative explanations against observed empirical patterns (Fearon, 1991; Bennett & Checkel, 2015). We evaluate whether competing hypotheses would produce documented operational signatures.

Diplomatic Coercion Only: This hypothesis fails due to temporal compression. Coercive diplomacy produces gradual compliance measures over extended periods as targets negotiate concessions while seeking to preserve core interests (Freedman, 2003; Schelling, 1966). Successful coercion requires iterative signaling, credible threat communication, and observable compliance steps. The Syrian collapse exhibited instantaneous operational paralysis within an 11-day window, with no diplomatic announcements preceding collapse and no evidence of negotiated terms. This pattern contradicts established models of how diplomatic pressure induces behavioral change.

Internal Military Coup: Standard coup dynamics predict factional contestation over media outlets as competing groups seek to establish legitimacy, competing command directives from rival centers as different factions mobilize supporters, and partial continuity of military operations by the coup faction seeking to demonstrate governing capacity (Powell, 2003; Quinlivan, 1999). The Syrian case exhibited systemic command silence without competing directives, complete cessation of air operations (rather than continuation under new authority), and no coup announcement or factional claims. Most diagnostically, Assad’s extraction to Moscow rather than internal detention or elimination contradicts coup logic entirely.

Opposition Military Victory: Military victories through battlefield conquest produce specific signatures: protracted urban combat with attritional casualties, visible turning points where offensive operations breach defensive lines, and gradual territorial conquest as victorious forces consolidate gains while overcoming resistance (Pollack, 2015). Instead, cities surrendered without significant combat, regime evaporated ahead of decisive engagements, opposition forces entered Damascus unopposed, and no major battles occurred during final 11 days. Collapse preceded rather than followed military pressure—a temporal sequence fundamentally incompatible with battlefield defeat explanations.

Economic Collapse Triggering Regime Failure: Economic deterioration in Syria had been ongoing for years, with severe resource constraints, hyperinflation, and institutional degradation creating chronic regime weakness (Lesch, 2012). Economic collapse models predict gradual degradation over months or years as cumulative pressures erode regime capacity, with visible indicators including salary non-payment triggering mass desertions and humanitarian crisis intensification. The actual collapse pattern contradicts these expectations. Elite evacuations preceded rather than followed economic crisis, occurring at specific moment (72 hours pre-collapse) suggesting planning rather than spontaneous reaction. Air operations ceased through external decision rather than fuel shortage. Command paralysis resulted from communication disruption rather than economic incapacity.

Multiple Independent Causes Converging: This hypothesis has merit in explaining regime vulnerability but cannot account for operational mechanism and temporal concentration. Multiple independent causes producing simultaneous effects would exhibit sequential rather than synchronized impacts, distributed rather than centralized timing, and mixed operational signatures reflecting diverse causal mechanisms. Instead, observed pattern shows simultaneous disruption across five independent domains, precise temporal synchronization within 11-day window, unified operational signatures consistent with single-source coordination, and centralized timing compression characteristic of planned operations.

The counterfactual testing strengthens confidence in the intelligence-led displacement hypothesis by demonstrating that no alternative explanation adequately accounts for the full spectrum of observable evidence. Each competing hypothesis fails specific diagnostic tests, with failures concentrated in areas where intelligence operations would leave distinctive signatures: temporal compression, multi-domain coordination, elite management, and international acquiescence.

- THE OPERATIONAL EXECUTION

- Four-Phase Operational Model

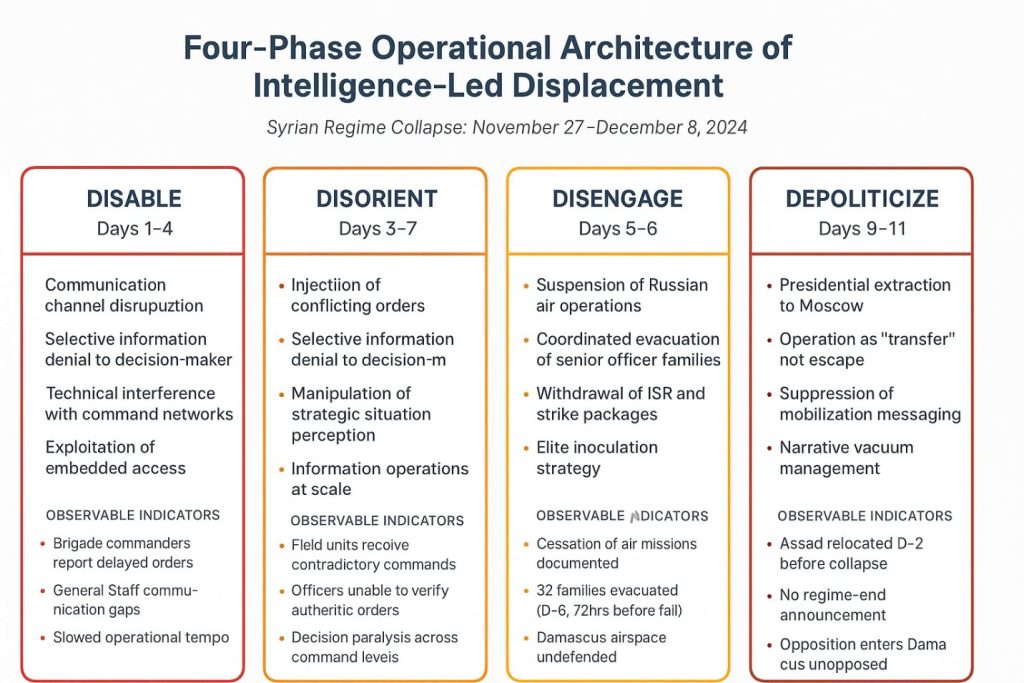

The operation proceeded through four coordinated phases, each building cumulative paralysis that rendered resistance increasingly futile:

PHASE 1 – DISABLE (Days 1-4): Communication disruption between presidential palace and General Staff created order latency without triggering immediate alarm. Brigade commanders reported delayed instructions; officers awaited orders that never arrived. This phase targeted the apex of the command pyramid—linkages between political leadership and military execution—slowing the regime’s ability to respond to developing threats while avoiding detection (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008). The operational objective was degrading decision coherence sufficiently to prevent effective defensive coordination while remaining subtle enough to avoid triggering countermeasures.

Mechanisms employed included communication channel disruption, technical interference with command networks, selective information denial to key decision-makers, and exploitation of embedded access to command protocols. Observable indicators included brigade commanders reporting delayed orders, General Staff communication gaps, officers awaiting instructions, and slowed operational tempo at central command. Critical success factors were embedded technical access to Syrian command systems, knowledge of communication protocols, and authority to manipulate information flows.

PHASE 2 – DISORIENT (Days 3-7): Injection of contradictory directives from multiple apparent sources created decision paralysis. Field units receiving conflicting commands defaulted to inaction, unable to verify authentic orders. This phase amplified effects of Phase 1 by flooding surviving communication channels with contradictory information, making it impossible for mid-tier commanders to distinguish authentic orders from manipulated signals (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008).

Mechanisms included injection of conflicting orders from multiple apparent sources, contradictory tactical directives, bombardment of senior officers with inconsistent information, and manipulation of perception regarding strategic situations. Observable indicators were field units receiving contradictory commands, officers unable to verify authentic orders, mid-tier commanders paralyzed by uncertainty, and no coherent operational picture emerging. Success required capacity to impersonate legitimate command sources, understanding of command decision-making processes, and ability to sustain information operations at scale.

PHASE 3 – DISENGAGE (Days 5-9): Withdrawal of Russian air operations removed critical force multiplier (Trenin, 2018). Concurrent evacuation of 32 senior officer families (Day 3) fundamentally altered elite incentive structures—resistance risked annihilation while accommodation offered survival (Quinlivan, 1999). This phase removed critical enablers compensating for Syrian Arab Army weaknesses and created conditions where non-resistance became rational choice.

Mechanisms employed included suspension of Russian air operations across all fronts, coordinated evacuation of senior officer families, withdrawal of ISR and strike packages, removal of air cover from Damascus, Aleppo, and Idlib, and elite inoculation through preemptive extraction. Observable indicators were cessation of Russian air missions documented, Damascus airspace left undefended, mass evacuation of security elite families 72 hours before fall, officers recognizing lack of air support, and psychological impact of elite departures. Success factors included direct control of air operations, authority over evacuation logistics, access to personnel and family rosters, and secure corridors for movements.

PHASE 4 – DEPOLITICIZE (Days 9-11): Assad’s extraction to Moscow (Day 2 before collapse) prevented martyrdom dynamics. Absence of regime-end declarations maintained narrative vacuum, normalizing stand-down across security apparatus (Galeotti, 2019). This phase managed regime’s terminal moments to prevent uncontrolled outcomes and ensure controlled rather than chaotic termination.

Figure 2. Four-phase operational architecture of intelligence-led displacement during the Syrian regime collapse (November 27–December 8, 2024).

Mechanisms included presidential extraction to Moscow two days before collapse, operation characterized as “transfer” not escape, absence of regime end declaration, no mobilization calls to loyalists, and suppression of messaging that could trigger resistance. Observable indicators were Assad relocated to Moscow on Day -2, no public regime-end announcement, absence of loyalist last-stand mobilization, narrative space left deliberately ambiguous, and opposition entry into Damascus unopposed. Critical success factors were diplomatic channels for leader reception, authority to arrange international transit, capacity to neutralize factional vetoes of extraction, and control of information environment.

Each phase required capabilities only comprehensive patron embedding could provide: technical command integration, air operations authority, personnel roster access, and diplomatic transit coordination. The phased approach demonstrates operational discipline characteristics of professional intelligence services (Richelson, 2007). Each phase was built upon previous, creating cumulative effects that rendered resistance increasingly futile. The progression from command disruption to information chaos to force withdrawal to leader extraction represents systematic dismantling of regime’s coercive architecture.

- Synchronization Mechanisms

The operation’s effectiveness derived from simultaneous action across five independent domains, creating systemic effects that overwhelmed regime capacity for adaptation (Hoffman, 2007; Galeotti, 2019). The synchronization required to execute these five-domain operations simultaneously reveals sophisticated operational planning and comprehensive access (Burt, 1992; Hafner-Burton et al., 2009). Each domain required different capabilities, operated under different authorities, and involved different personnel networks. Coordinating their simultaneous execution without visible command structure or public communication demonstrates operational sophistication associated with elite intelligence services rather than improvised internal coups or spontaneous opposition advances.

- THE ALLIANCE OF SILENCE

- Strategic Interest Alignment Without Formal Coordination

The “alliance of silence” functioned through aligned interests rather than formal coordination (Goddard, 2010). Each major power extracted net benefits from collapse while avoiding costs of counter-intervention:

Russia: Achieved strategic paradox—retained Mediterranean bases (Tartus, Hmeimim) while shedding costly, unreliable client (Trenin, 2018; Crawford, 2011). Moscow faced costly subsidization of unreliable client, Iranian institutional overreach diluting Russian influence, resource drain amid Ukraine commitments, Assad exploring back-channels with Washington, and diminishing returns on continued investment (Giles, 2019). Collapse enabled Russia to reduce financial burden, curtail Iranian institutional drift, reallocate resources to priority theaters, retain strategic bases, maintain regional leverage via control of “off switch,” and establish precedent for client management. Post-collapse force reallocation to Ukraine theater demonstrated priority recalibration. Net calculation: strongly positive. Benefits substantially exceeded costs; managed transition preserved core interests while eliminating liabilities (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991).

Iran: Confronted strategic loss but lacked viable counter-intervention options. Tehran was dependent on Russian airspace control for logistics, faced investment in Syrian institutions threatened by collapse, loss of strategic depth versus Israel, and risk to land corridor to Hezbollah. Military confrontation with Russia over Syria was infeasible given comprehensive Russian airspace dominance and exposure of Iranian forces without air cover (Trenin, 2018). Regional isolation if acting alone and resource expenditure in unwinnable scenario made counter-intervention prohibitively costly. Tehran accepted regime termination while securing tacit guarantees for militia network preservation and post-collapse role in reconstituted authority. Net calculation: moderately negative but mitigated through managed transition. Losses were real but managed; preservation of networks and post-collapse influence reduced damage; counter-intervention would have worsened position.

Turkey: Capitalized on Russian airspace withdrawal to advance Kurdish territorial objectives and border security. Ankara faced Kurdish autonomous region on border, refugee crisis management, and limited influence over Syrian trajectory under Assad-Russia-Iran dominance. Collapse provided opportunity to address Kurdish territorial control, reduce Assad-PKK cooperation, enhance leverage over post-collapse arrangements, and improve border security. The critical enabler was tacit Russian acquiescence: Moscow’s withdrawal of Syrian air power created permissive environment for Turkish border operations that would previously have risked Russian retaliation. Net calculation: positive. Turkey advanced priority objectives (Kurdish issue, border security) at minimal cost; tacit coordination with Russia enabled gains without confrontation.

United States: Achieved preferred outcome (Assad removal) through preferred method (minimal U.S. role). Washington desired Assad removal without direct intervention, faced risk of Iranian-Russian consolidation, commitment to burden-sharing with regional partners, and avoidance of Iraq-style post-intervention obligations (Lesch, 2012). Collapse achieved regime change without U.S. military action, avoided overt ownership and accountability, shifted burden to regional actors, disrupted Iranian influence corridor, and demonstrated limits of Russian commitment to clients. The quiet diplomatic coordination suggests Washington was informed of Russia’s intentions and signaled non-interference but avoided formal involvement generating attribution or accountability (Poznansky, 2020). Net calculation: positive. United States achieved preferred outcome through preferred method; risks and costs externalized to regional actors.

- Deconfliction Mechanisms and Threshold Signaling

The operation succeeded through sophisticated deconfliction mechanisms preventing misunderstanding and escalation (Goddard, 2010; Schelling, 1966). Three mechanisms proved critical:

Non-Attribution Pact: No major power claimed responsibility for Assad’s removal. Significantly, no power accused Russia of engineering collapse despite Moscow’s obvious capacity and motive. This collective silence served all actors’ interests: Russia avoided reputation damage as unreliable patron, Iran escaped blame for failing to protect client, Turkey denied responsibility for enabling opposition advances, and United States maintained non-intervention posture (Poznansky, 2020). The absence of attribution claims or counter-claims suggests advance understanding that all parties would maintain operational ambiguity.

Tacit Guarantees: Intelligence reporting and diplomatic sources indicate quiet commitments were communicated through back-channels before and during collapse. Iran received assurances that militia networks would not be systematically targeted in immediate aftermath. Russia communicated continued base presence expectations. Turkey secured understanding regarding permissible scope of border operations. United States signaled acceptance of Russian base retention and managed transition. These guarantees were never formalized in documents or public statements, but their existence can be inferred from subsequent behavior: Iran’s non-mobilization, Russia’s base security, Turkey’s limited border operations, and U.S. diplomatic silence.

Threshold Signaling: The operational sequence itself communicated intentions and limits (Schelling, 1966). Russia’s withdrawal of air cover signaled regime termination but did so gradually enough (D-10 through D-5) to allow other actors to recognize the pattern and adjust postures. Evacuation of elite families (D-3) sent unmistakable signals that leadership extraction was imminent, giving regional actors final opportunity to position for post-collapse environment. Assad’s departure to Moscow (D-2) clarified that transition would be managed rather than chaotic, reducing fears of power vacuum and uncontrolled violence that might trigger intervention.

The deconfliction architecture enabled what Goddard (2010) terms “embedded restraint”—where great powers recognize and respect each other’s priority spheres of influence through demonstrated forbearance rather than explicit treaties. In Syria’s case, restraint manifested as coordinated non-intervention: each power capable of disrupting the operation chose not to do so, with choices timed and calibrated to signal acceptance rather than oversight or indecision.

- VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

- Structural Vulnerabilities Enabling Intelligence-Led Displacement

The Syrian case identifies structural characteristics that enabled engineered collapse, providing diagnostic framework for assessing regime vulnerability in other externally dependent states. Externally dependent regimes face heightened intelligence-led displacement risk when exhibiting:

Centralized Command Architecture: Highly centralized decision-making with single apex and no redundancy creates exploitable paralysis points (Quinlivan, 1999). Syria exhibited all orders flowing through palace and General Staff with no autonomous operational authority at lower levels. When external actors can access or paralyze the apex node, entire military apparatus becomes disabled. Distributed command architectures with empowered regional commanders can adapt to headquarters incapacitation through horizontal coordination; centralized architectures collapse entirely when center fails (Burt, 1992).

Single-Patron Security Dependence: Complete reliance on one patron for critical capabilities (air power, intelligence, logistics) grants that patron an “off switch” for regime military capacity (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991). Syria’s absolute dependence on Russian air power meant Moscow controlled regime survival (Trenin, 2018). No indigenous air force could substitute; no alternative patron could provide equivalent capabilities on requisite timelines. This dependency was not inevitable but resulted from decades of Soviet/Russian military aid, Syrian strategic choices regarding force structure, and economics of maintaining modern air forces.

Deep Patron Embeddedness: Foreign advisors throughout command structure with operational control over key nodes provides manipulation infrastructure (Hafner-Burton et al., 2009; Nexon & Wright, 2007). Embedded advisors improve tactical effectiveness, technical integration enhances operational coordination, and shared decision-making processes align strategies. Yet each integration step grants patron visibility, influence, and ultimately control over critical systems. By the time client regimes recognize vulnerability, reversing relationships requires capabilities they no longer possess independently. Syrian-Russian military integration evolved over nine years, creating dependencies that became irreversible without accepting massive short-term capability loss (Trenin, 2018).

Extreme Personalist Coup-Proofing: Security apparatus with loyalty concentrated around individual leader rather than institutions makes regime vulnerable when that individual can be neutralized or extracted (Quinlivan, 1999; Powell, 2003). Assad’s security apparatus concentrated loyalty through sectarian solidarity (Alawite dominance of officer corps), material benefits (privileged status and corruption opportunities), and mutual complicity (shared responsibility for regime violence). This personalization prevented internal coups but meant elite calculus changed instantly when Assad’s survival was no longer assured.

Declining Strategic Value to Patron: When client regime’s utility falls below cost of continued patronage amid rising maintenance costs, patron recalibration becomes likely (Crawford, 2011; Lake, 2009). Moscow’s documented frustrations with Assad’s governance by 2024—Iranian institutional overreach, economic unsustainability, back-channel exploration with Washington—created incentives for regime change rather than regime preservation (Trenin, 2018; Giles, 2019).

Syria exhibited all five factors simultaneously, explaining collapse completeness. Regimes scoring 4+ factors face high vulnerability.

- Resilience Measures for Vulnerable Regimes

Vulnerable regimes can implement systematic defensive countermeasures to reduce susceptibility:

Command Redundancy (Critical Priority): Establish multiple command centers with independent communications. Distribute operational authority to regional commanders. Create succession protocols maintaining continuity. Enable autonomous unit operations during communication breakdown. Regular testing of backup systems. This directly addresses command paralysis vulnerability by ensuring apex paralysis does not cascade throughout military structure (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008).

Communication Security (Critical Priority): Deploy multiple independent communication networks (military, government, emergency). Implement robust encryption across all sensitive channels. Establish air-gapped backup systems. Create mesh networks resistant to centralized disruption. Regular counterintelligence sweeps. This prevents communication manipulation central to intelligence-led operations (Hughes, 2017).

Diversified Security Partnerships (High Priority): Cultivate multiple external security relationships. Avoid single-patron dependency for critical capabilities. Develop indigenous air power and ISR capabilities. Maintain alternative sources for military equipment. Balance competing patron interests strategically. This reduces catastrophic single-point dependency enabling patron to control absolute “off switch” (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991).

Counterintelligence Enhancement (High Priority): Regular audits of foreign advisor access and authorities. Compartmentalize sensitive operations from external actors. Monitor patron intelligence collection activities. Protect elite families and personnel from external leverage. Establish internal security protocols. This addresses patron embeddedness vulnerability by limiting foreign advisor access to sensitive operations (Richelson, 2007; Patton, 2015).

Institutional Depth (Moderate-High Priority): Build security institutions beyond personality-dependent structures (Quinlivan, 1999; Powell, 2003). Create collective leadership mechanisms. Establish clear succession and continuity protocols. Reduce concentration of power in single individuals. Strengthen institutional rather than personal loyalty. However, this requires fundamental governance reforms that are difficult to implement in authoritarian contexts (Brownlee, 2007).

Indigenous Capability Development (Moderate Priority): Invest in domestic defense industrial base. Develop indigenous air power, ISR, and electronic warfare. Reduce technical dependencies on foreign systems. Train domestic personnel to operate critical systems. Create sufficient self-maintenance and support. However, this requires long-term investment and industrial capacity beyond reach of most vulnerable regimes.

No set of countermeasures can provide absolute protection against determined intelligence operations by capable powers. Vulnerability reduction rather than elimination represents realistic objective. Regimes scoring high on vulnerability indicators should prioritize measures with highest expected effectiveness relative to implementation complexity and resource requirements.

- THEORETICAL AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS

- Silent Regime Change as Distinct Category of Statecraft

The Syrian case establishes intelligence-led displacement as distinct modality of twenty-first-century statecraft, differentiated from conventional regime change through operational mechanisms, attribution complexity, and outcome characteristics (Johnson, 1996; Godson, 1989; Poznansky, 2020). Traditional regimes change modalities—military invasion, popular revolution, internal coup, economic collapse—operate through visible processes subject to public scrutiny and accountability. Intelligence-led displacement achieves regime transformation through mechanisms designed for deniability, creating strategic environment where consequential decisions about governance occur beyond democratic oversight.

This transformation poses profound questions for international order. Traditional norms governing intervention—prohibitions on aggressive war, respect for sovereignty, accountability for civilian harm—presume visible state action subject to public scrutiny and legal judgment (Poznansky, 2020). When regime change occurs through mechanisms designed for deniability, these restraints erode. No UN Security Council debates intervention, no media documents casualties, no domestic constituencies demand justification, no international courts assess legality.

This erosion creates strategic moral hazard: if covert displacement proves effective, low-cost, and consequence-free for intervening power, rational actors will increasingly prefer it to diplomatic engagement or transparent military action. The result is geopolitical environment where small states face perpetual uncertainty about patron reliability, where intelligence services accumulate unchecked influence over foreign governance, and where architectural decisions of global order occur in shadows beyond democratic oversight (Johnson, 1996).

- The Patron-as-Executor Paradox

The research reveals critical vulnerability in asymmetric patron-client relationships: the same embedded access enabling external powers to protect client regimes simultaneously creates infrastructure for their termination (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991; Burt, 1992). This paradox challenges conventional alliance theory and illuminates previously underexamined risks facing externally dependent authoritarian states.

Traditional alliance theory assumes patron reliability correlates with strategic interest alignment: when patrons benefit from client survival, they provide support; when interests diverge, patrons withdraw support but rarely actively terminate clients (Crawford, 2011). The Syrian case demonstrates that deep embedding enables third option: active neutralization preserving patron assets while eliminating problematic leadership (Trenin, 2018; Giles, 2019). Russia retained Tartus and Hmeimim bases while terminating Assad, achieving strategic continuity through regime discontinuity.

This dynamic fundamentally recasts understanding of patron reliability and client sovereignty. Client regimes accepting deep patron integration for short-term security gains accumulate long-term vulnerabilities that cannot easily be reversed. Once command structures, technical systems, and operational protocols are integrated with external patrons, attempts to reduce dependency risk immediate capability loss that hostile actors will exploit (Hafner-Burton et al., 2009; Nexon & Wright, 2007). The patron-client relationship becomes structurally irreversible even when strategically undesirable.

- Intelligence Services as Autonomous Geopolitical Actors

The research positions intelligence agencies not as auxiliary instruments of foreign policy but as autonomous architects of geopolitical transformation (Johnson, 1996; Godson, 1989; Galeotti, 2019). Traditional international relations theory treats intelligence services as subordinate tools—collecting information for policymakers, executing discrete operations supporting broader strategies, managing clandestine networks as one capability among many. The Syrian case suggests qualitative transformation: intelligence services as prime movers in geopolitical change, not merely informing decisions but making them, not supporting policy but becoming it.

This transformation poses profound questions for democratic governance and international stability. If most consequential decisions about war, peace, and regime survival occur within intelligence bureaucracies operating beyond legislative oversight, executive accountability, or public awareness, what remains of democratic control over foreign policy? If small states exist at sufferance of great power intelligence services that can terminate governance structures at will, what meaning does sovereignty retain? (Poznansky, 2020)

The Syrian collapse—silent, coordinated, devastatingly effective—stands as both achievement and warning. It demonstrates that twenty-first-century power increasingly flows through invisible channels: control of networks rather than territory, manipulation of perceptions rather than destruction of armies, orchestration of outcomes rather than declaration of intentions (Hoffman, 2007; Galeotti, 2019). This is power that leaves no monuments, signs no treaties, and claims no credit. It manifests only in sudden absence where a state once stood, in silence where commands once echoed, in darkness where regime lights blink out without explanation.

- Precedent and Replication Risks

The Syrian precedent establishes a playbook that other powers will study and adapt (Richelson, 2007). Regional actors with intelligence capabilities—Turkey, Iran, Gulf states, Israel—may pursue similar strategies against adversaries or unstable neighbors. Major powers managing client relationships in contested regions—Russia in Africa and post-Soviet space, China in Central Asia, United States in Latin America and Middle East—now possess demonstrated model for low-cost regime recalibration.

Yet diffusion of this model will generate counter-adaptations. Vulnerable regimes will invest in resilience architectures: diversified security partnerships avoiding single-point dependencies, redundant command systems resistant to external disruption, enhanced counterintelligence detecting patron penetration, and hardened civilian authority structures functioning despite elite decapitation (Quinlivan, 1999; Powell, 2003). Most sophisticated responses will likely emerge from regimes with advanced intelligence capabilities of their own, who recognize threat because they possess similar offensive capacities.

The resulting dynamic—offensive innovation in covert displacement competing with defensive resilience measures—will shape significant dimension of twenty-first-century statecraft (Hoffman, 2007; Galeotti, 2019). The advantage lies with offensive actors in near term, as patron relationships already established contain access pathways enabling future operations. Over time, however, diffusion of countermeasures and increased vigilance may raise difficulty and cost of intelligence-led regime change, potentially restoring some equilibrium to patron-client relations (Crawford, 2011; Lake, 2009).

- CONCLUSION

- Summary of Findings

This study investigated sudden collapse of Syrian regime as case of intelligence-led displacement, examining how covert operations engineer state failure without conventional military defeat. Through systematic analysis of operational timelines, attribution frameworks, and counterfactual diagnostics, the research established several key findings.

First, Syria’s collapse exhibited signatures of coordinated intelligence-induced decapitation rather than organic regime failure, military defeat, or spontaneous popular uprising. Temporal clustering of disruptions across five operational domains within eleven-day window, precision of elite family evacuations 72 hours before capital fall, and synchronized withdrawal of Russian air power across all fronts collectively point toward centralized orchestration by actor with comprehensive embedded access to regime infrastructure (Heuer, 1999; Bennett & Checkel, 2015).

Second, Russia’s GRU emerges as probable architect based on convergent evidence across three dimensions: capacity (years of embedded advisory presence, control of Syrian airspace, technical integration with command systems), motive (strategic imperatives to reduce Syrian costs, curb Iranian overreach, reallocate resources to Ukraine theater), and operational signature (non-kinetic methods, access-enabled disruption, controlled leadership extraction, deniability architecture) (Trenin, 2018; Giles, 2019; Galeotti, 2019; Richelson, 2007). While absolute attribution remains unattainable by design, convergence of evidence supports high confidence (75-85% probability) in this assessment.

Third, “alliance of silence” among major powers—Russia, Iran, Turkey, and United States—enabled regime termination through tacit deconfliction rather than formal coordination (Goddard, 2010; Schelling, 1966). Each actor secured strategic benefits while avoiding public accountability: Russia retained bases while shedding client costs, Iran preserved militia networks despite leadership loss, Turkey advanced Kurdish agenda, and United States achieved collapse without intervention burden (Crawford, 2011; Lake, 2009; Poznansky, 2020).

Fourth, operational architecture employed four-phase model—DISABLE (command disruption), DISORIENT (information manipulation), DISENGAGE (force withdrawal and elite evacuation), DEPOLITICIZE (leadership extraction and narrative management)—that systematically incapacitated regime resistance capacity without kinetic confrontation (Wirtz & Larsen, 2008; Galeotti, 2019). This phased approach reveals sophisticated intelligence tradecraft and comprehensive understanding of how modern command structures function and can be paralyzed.

Fifth, Syrian case establishes structural vulnerabilities enabling intelligence-led displacement: centralized command architectures creating single points of failure, external security dependencies granting patrons “off switches,” deep patron embedding providing access to critical systems, extreme coup-proofing concentrating loyalty around individuals rather than institutions, and single-patron relationships eliminating alternative support options (Quinlivan, 1999; Lake, 2009; Burt, 1992; Powell, 2003).

- Theoretical Contributions

The concept of “silent regime change” establishes intelligence-led displacement as distinct category of twenty-first-century statecraft, differentiated from conventional regime change modalities (military invasion, popular revolution, internal coup, economic collapse) by operational mechanisms, attribution complexity, and outcome characteristics (Johnson, 1996; Godson, 1989; Poznansky, 2020). This conceptual innovation provides scholars and policymakers with analytical tools for understanding regime changes that defy conventional explanatory frameworks.

The “patron-as-executor paradox” challenges conventional alliance theory by demonstrating that protection mechanisms become termination pathways when patrons achieve sufficient embedded access (Lake, 2009; Morrow, 1991; Crawford, 2011). Traditional theory treats patron abandonment as withdrawal of support; this study shows deep integration enables active neutralization, fundamentally recasting security dilemma facing externally dependent states. Client regimes must balance immediate capability gains from patron integration against long-term vulnerability accumulation that may become irreversible (Burt, 1992; Hafner-Burton et al., 2009; Nexon & Wright, 2007).

The “alliance of silence” framework introduces tacit multilateral deconfliction as mechanism for great power coordination on regime change without formal agreements or public declarations (Goddard, 2010; Schelling, 1966). This finding contributes to literature on crisis management and great power politics by documenting how competing powers achieve convergent outcomes through operational choices—withdrawn air cover, opened corridors, coordinated non-intervention—that signal intentions and limits without requiring explicit negotiation or public commitment.

Methodologically, the study advances frameworks for analyzing covert operations under conditions of intentional opacity. The convergent indicator approach—triangulating testimonies, operational signatures, temporal clustering, and counterfactual tests—provides replicable tools for intelligence studies scholarship confronting inherent evidentiary constraints. This methodological innovation enables rigorous analysis of phenomena designed to evade detection, balancing scholarly standards with operational realities.

- Policy Implications

For policymakers in vulnerable Regimes, the research provides actionable vulnerability assessment frameworks and resilience measures. The diagnostic checklist identifying structural risk factors—command centralization, external security dependence, patron embeddedness, extreme coup-proofing, communication vulnerabilities, declining strategic value to patron—enables systematic evaluation of regime exposure to intelligence-led displacement. Regimes exhibiting multiple high-risk factors should prioritize command redundancy, communication security, counterintelligence enhancement, and security partnership diversification as immediate defensive measures.

For international institutions and oversight bodies, the findings highlight accountability deficits when consequential regime changes occur through mechanisms designed for deniability. Strengthening fact-finding mandates capable of operating under constrained access, reinforcing strategic coherence review for Regimes conducting covert action, and clarifying escalation and sovereignty norms for non-kinetic interventions represent priority areas for institutional development. The current normative vacuum enables intelligence operations that produce regime displacement without triggering traditional restraints on aggression.

For intelligence studies scholars, the Syrian case provides empirical foundation for developing signature libraries of intelligence-led operations, enabling pattern recognition across contexts. The operational characteristics documented here—command disarticulation, force-multiplier withdrawal, elite inoculation, leadership extraction, multilateral deconfliction—offer diagnostic criteria for identifying similar operations in Africa, post-Soviet space, Latin America, and other regions where great powers manage client relationships through intelligence channels.

- Limitations and Future Research

The study acknowledges inherent limitations when analyzing operations designed for deniability. Absolute attribution remains unattainable by design; the analysis therefore advances disciplined inference based on convergent probability rather than definitive proof. Testimonial evidence derives from sources with potential self-interest in shaping narratives, requiring critical evaluation rather than uncritical acceptance. The absence of internal GRU documentation means attribution must rely on external signatures and pattern recognition rather than direct confirmation. Classification of intelligence materials by all relevant governments means publicly available evidence represents only partial view of operational reality.

Future research should pursue four directions. First, comparative case analysis applying this framework to other suspected intelligence-led displacements (Libya 2011, Ukraine 2014, potential African and post-Soviet cases) would strengthen pattern libraries and refine attribution methodologies. Second, investigation of failed displacement attempts, or successful resistance cases would identify defensive measures proving effective in practice, complementing the theoretical resilience frameworks developed here. Third, network mapping reconstructing advisory interfaces, technical integration pathways, and operational coordination mechanisms in patron-client relationships would provide more granular understanding of how embedded access accumulates over time. Fourth, analysis of post-collapse outcomes—how power vacuums are managed, whether tacit guarantees hold, what governance structures emerge—would complete the causal narrative and assess whether intelligence-led displacement produces more stable outcomes than conventional regime change.

- Final Reflection

The architecture of silence documented in this study represents both culmination and preview: the maturation of intelligence-led Regimecraft as established capability and the anticipation of future deployments in contested regions worldwide. When Damascus fell without battle, when command structures dissolved without resistance, and when a client Regime evaporated while its patron remained silent, the event signaled not chaos but precision—the triumph of intelligence tradecraft over conventional force, of access over armies, of orchestrated paralysis over open confrontation.

Understanding this power—its mechanisms, its limits, its implications—represents one of the central challenges for contemporary scholarship and policymaking. This study offers an initial framework, but the phenomenon it examines is evolving rapidly. As intelligence agencies refine their tradecraft, as vulnerable Regimes develop countermeasures, and as great powers test the boundaries of covert Regimecraft, the architecture of global order will be reshaped not by the visible movements of armies and diplomats but by the unseen hand of intelligence operations designed to leave no trace.

The Syrian endgame, then, is not merely history but prophecy—a preview of conflicts to come, conducted in shadows, decided in silence, and understood only after the fact, when analysts sift through the rubble of a Regime that fell without a battle, searching for fingerprints on a weapon no one will admit to wielding. In today’s geopolitics, the most decisive power is often the one that leaves no trace.

APPENDIX.

CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL DEFINITIONS

| Concept | Category | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Convergent indicator analysis | Research Method | A structured inference technique that evaluates whether multiple independent indicators point toward the same underlying phenomenon. When disparate data streams converge on a single explanation, confidence in that explanation increases—especially in opaque, contested, or data-poor environments. Widely used in intelligence studies, political science, and crisis diagnostics. |

| Tradecraft signature analysis | Intelligence Studies Method | An attribution approach that identifies operational fingerprints characteristic of a specific intelligence service. Analysts compare observed behaviors, procedural patterns, and operational techniques with known historical signatures to infer likely responsibility even when direct evidence is unavailable. Central to covert action analysis and counterintelligence. |

| Counterfactual diagnostic testing | Analytical Approach | A causal-inference method that tests whether alternative explanations could plausibly produce the observed outcome. By constructing hypothetical “what-if” scenarios, analysts assess which causal pathways remain viable and eliminate those inconsistent with empirical patterns. Strengthens inference in complex political and security environments. |

| Structured analytic techniques (Heuer) | Intelligence Methodology | A family of systematic procedures designed to reduce cognitive bias and improve analytic rigor. Techniques include competing hypotheses, key assumption checks, and indicator analysis. Developed by Richards Heuer, SATs are now standard across intelligence communities for high-stakes decision-making. |

| Alliance of silence | Theoretical Contribution | A form of tacit coordination in which multiple states converge on a shared outcome without formal agreements or public signaling. Instead of explicit cooperation, states align through mutual restraint, non-interference, and parallel actions that collectively shape political outcomes while preserving deniability. |

| Patron-as-executor paradox | Theoretical Contribution | A paradox in which a patron state that once protected a client regime becomes the actor most capable of orchestrating its removal. The same embedded access, advisory presence, and structural leverage that ensured regime survival can be repurposed into mechanisms of termination. Highlights the dual-use nature of patron-client dependency. |

| Silent regime change | Theoretical Contribution | A modality of externally induced political transition achieved without open conflict, visible coups, or public declarations. Regime collapse occurs through engineered paralysis of command, withdrawal of critical enablers, and controlled elite extraction, relying on non-kinetic, intelligence-driven mechanisms. |

| Elite inoculation | Operational Strategy | A strategy in which key regime elites and their families are preemptively protected or evacuated to neutralize incentives for resistance. By securing personal safety, external actors reduce the likelihood of spoilers or loyalist mobilization during a managed transition. Common in coup-proofing and intelligence-led regime change. |

| Command disarticulation | Military/Operational Concept | The deliberate disruption of linkages between political leadership, military command, and operational units. When communication channels, verification protocols, or decision nodes are disabled, military units retain physical capability but lose functional direction, producing systemic paralysis without kinetic confrontation. |

References

Adamsky, D. (2015). Cross-domain coercion: The current Russian art of strategy. Proliferation Papers, 54. Paris: IFRI Security Studies Center.

Badawi, H. (2025). The Twelve Days of Dissolution: Ibn Khaldun’s theory of state cycles and the swift collapse of the Syrian regime. Journal of Islamic Civilization and Culture Review, 1(1), Article 30. https://ejournal.foundae.com/index.php/jiccr/article/view/30

Bennett, A., & Checkel, J. T. (Eds.). (2015). Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool. Cambridge University Press.

Brownlee, J. (2007). Authoritarianism in an age of democratization. Cambridge University Press.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Harvard University Press.

Crawford, T. W. (2011). Preventing enemy coalitions: How wedge strategies shape power politics. International Security, 35(4), 155-189.

Fearon, J. D. (1991). Counterfactuals and hypothesis testing in political science. World Politics, 43(2), 169-195.

Freedman, L. (2003). The evolution of nuclear strategy (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

Galeotti, M. (2019). Russian political war: Moving beyond the hybrid. Routledge.

Giles, K. (2019). Moscow rules: What drives Russia to confront the West. Brookings Institution Press.

Goddard, S. E. (2010). Indivisible territory and the politics of legitimacy: Jerusalem and Northern Ireland. Cambridge University Press.

Godson, R. (Ed.). (1989). Intelligence requirements for the 1990s: Collection, analysis, counterintelligence and covert action. Lexington Books.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., Kahler, M., & Montgomery, A. H. (2009). Network analysis for international relations. International Organization, 63(3), 559-592.

Heuer, R. J. (1999). Psychology of intelligence analysis. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency.

Hoffman, F. G. (2007). Conflict in the 21st century: The rise of hybrid wars. Potomac Institute for Policy Studies.

Hughes, J. S. (2017). The role of attribution in cyber conflict. Journal of Cybersecurity, 3(2), 115-124.

Johnson, L. K. (1996). Secret agencies: U.S. intelligence in a hostile world. Yale University Press.

Lake, D. A. (2009). Hierarchy in international relations. Cornell University Press.

Lesch, D. W. (2012). Syria: The fall of the house of Assad. Yale University Press.

Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive authoritarianism: Hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

Morrow, J. D. (1991). Alliances and asymmetry: An alternative to the capability aggregation model of alliances. American Journal of Political Science, 35(4), 904-933.

Nexon, D. H., & Wright, T. (2007). What’s at stake in the American empire debate. American Political Science Review, 101(2), 253-271.